-

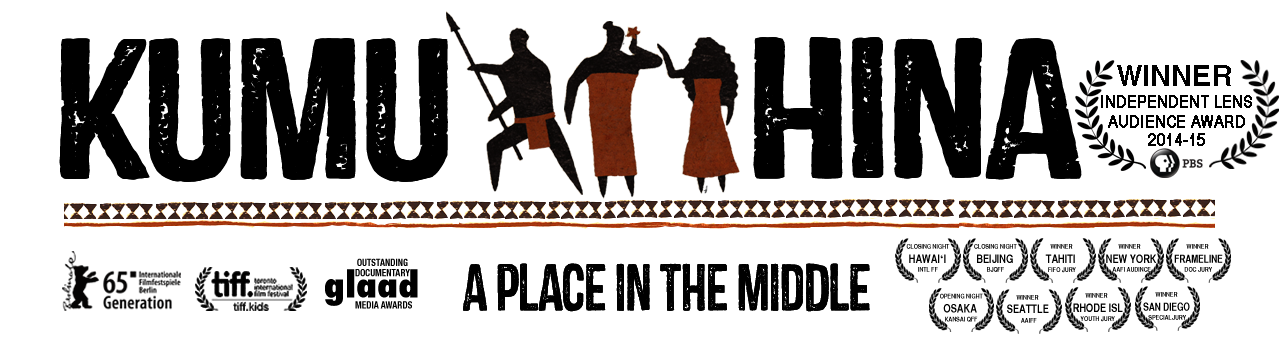

KUMU HINA: A Life of Aloha -- Modern Weekly, Guangzhou, China

- Posted on 9th Oct

- Category: news

Kumu Hina:我生命中的Aloha

9月15日,纪录片《Kumu Hina》在广州小范围放映。主角Hina是夏威夷一位传承传统文化的教师和社会活动家;同时她也是Mahu(玛胡)—现代西方语义中的“变性 人”;Hina身上还有一半中国血统。多元的文化交织融合,正体现Hina一直发扬的夏威夷传统精神内核:爱与包容。

提到夏威夷,你会联想到什么?或许是热带海滩、小麦色的皮肤,尤克里里琴和“Aloha”—这是在当地人们见面、道别的常用语,也有“我爱你”的意思。在 有一半中国血统的夏威夷人Hina(即Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu,黄贵光)看来,Aloha更是一种有夏威夷特色的生活理念:个体之间的平等,对于传统的尊重,以及对文化的包容。

以平等的名义

初见Hina,是在她纪录片的放映会上。她身穿着夏威夷风格的黄色碎花连衣裙、化上了柔美的妆容,展现出女性的姿态。Hina与在场的观众一起席地而坐,看着屏幕中自己的生活与回忆又一次展现。

在电影里,她在一家有夏威夷背景文化的中学里带领孩子排练当地传统歌舞两个多月。她说,舞蹈传承的夏威夷精神类似于中国的儒学、孔子精神,精练而内涵丰 富。排练前,学校要求男生戴上黄色的花圈,女生则戴上白色花环。一位叫Ho’onani的女生则要求同时戴上两种颜色的花环。Ho’onani是一位举止 打扮都很“男生”的女孩子,但是她说自己并不介意别人的眼光。她自己写了一首歌,歌词有一句“Mai Hilahila”,意思是不为自己感到羞耻。

在学校年终表演舞蹈Ai Ka Mumu中,男生和女生各自负责一个环节,男生的部分设定在火山爆发的场景之下体现出夏威夷岛国的传统,需要展现出极强的力量和爆发力,而 Ho’onani也希望参与其中。一次排练中所有人要举起双臂,而Hina则在他们手臂上施加压力,要求男生用力固定手臂不被压下去。这项任务中,却只有 Ho’onani完成了。Hina对着男生说:“现在表演是你们要展现Ku(男性力量)的时候,而你们面前站着的一个生理上的女生,她的Ku比你们所有人 都多。”

通过这种言传身教,Hina在传承Aloha这种包容与尊重个体的不同的核心精神。但其实Hina自己在学生时期还是因为举止过于女性化而没有很好地被身 边人接纳,受到了不少嘲笑。但母亲给她的一半夏威夷人血统和文化成了这种不理解的天然盾牌。Hina回忆小时候与自己婆婆一起的生活,说她从来没有介意过 自己的性别。2014年9月,Hina借纪录片在广州放映的机会找回了自己在广东中山的亲人,当Hina告诉亲人自己是一个Mahu的时候,亲人都感到震 惊,但过后他们对Hina说:“你是我们的亲人,不管你是夏威夷人还是中国人,是男的或者女的,你都是我们的一分子,我们同样爱你。”

家庭的包容培养了Hina性别平等的意识。“我是变性人吗?是的,用西方的标准来看的话。但我认可西方的标准吗?不。我会把自身建立于外来的规范之上去实 现自己的价值吗?不!” 2013年1月,夏威夷一份同性恋婚姻合法化的草案被提出,当时一些学者认为夏威夷传统文化和精神中并不存在同性恋这样的因素时,Hina作为一个植根于 夏威夷社区的市民,说出了自己和一众夏威夷市民的想法,支持同性恋婚姻合法化。直到2013年11月3日,夏威夷婚姻平等法案终于被正式通过。随后民众举 办了庆祝活动,并且邀请了Hina唱传统的夏威夷歌曲《Oli》作为开场。

以传统的名义

其实除了“玛胡”,夏威夷文化里还有Punalua(重婚,或一对兄弟与一对姐妹结婚)、Aikane(同性婚姻)等概念,这些都是个人生活方式的选择。可以说,男女平等也是整个夏威夷文化生态平衡中的重要一环。

除此之外,夏威夷还有许多特色文化。22岁的夏威夷女孩Paloke说很多年轻人也还是很喜欢夏威夷传统的神话故事。“我们看到月亮,会想起Hina(夏 威夷月亮女神),我们看到河与大海,会想起Kane(淡水之神)和Kanaloa(深海之神)。这些都是夏威夷的一部分。”然而这样的传统的延续在时代发 展中总是会受到冲击。由于Hina对夏威夷文化的精通,她被州长任命为瓦胡岛殉葬事务委员会的主席。2012年纪录片拍摄之时,檀香山当地正希望兴建地下 铁路工程,但根据夏威夷州的法例,工程开始前必须通过完整的AIS探测和侦察。Hina在委员会中极力追求工程的合法性,希望全程由瓦胡岛殉葬事务委员会 监测,最大限度地保护祖先的骨灰。会议上一位瓦胡岛的居民说:“对于我们的人民来说,祖先的遗骸并不只是这些骨头,而是我们与家族、与我们过去之间的联 系。”Hina对于传统的执着不仅仅存在于夏威夷,还有自己身上的中国血统。

小时候Hina的中国外婆经常会跟Hina讲许多逐渐消逝的中国传统的生活方式。比如Hina从小被教导要在长辈吃饭后才吃,还有新年的时候要倒茶和说吉 利的话,Hina至今仍懂得说“恭喜你”、“添福添寿”。这些传统也许不符合现代科学的标准,但里面承载的确实是家庭乃至社会文化的结晶。Hina的爸爸 和婆婆还会教她做年糕,并告诉她黏稠的年糕寓意着一家人紧紧地连在一起不分离,所以每个人至少吃一口。“这一切让我学会了用心、有耐性,投入感情和时间去 做一件事,是会让自己收获并成长的。”Hina的爸爸今年82岁了,Hina说当爸爸不能做年糕了,她将会负起家庭中这个责任。

以包容的名义

夏威夷的文化都植根于它成为美国领土以前当地的法律、土地和自然资源,但在1778年英国人库克船长登陆后,殖民的腥风血雨、外国人带来的传染病和众多外 来宗教的渗透不仅使夏威夷王国覆灭,成为了美国第51个州,也让夏威夷土著的数量锐减,文化消亡得几乎仅剩下表面的仪式。当地180万人里,2.4万人能 讲夏威夷语,但不足300人以之为母语。

由于夏威夷语本来并没有书写系统,是后来传教士用拉丁字母按照发音发展出来的,因而夏威夷文化更多是靠口头、肢体语言来表达,现在的一些美国大学提供教育却是从书本上去学习夏威夷语,免不了得其 形而不得其精髓。Ni’ihau岛是夏威夷群岛里唯一与外界联系极少的岛屿,上面的100多名居民均是夏威夷土著。Hina自小与当地的几位居民一起在 O’ahu(瓦胡岛)生活,因此在他们身边学习到了传统的夏威夷语言。后来Hina在高中和大学也有继续系统学习相关课程。“但是在商业和资本利益的冲洗 下,很多夏威夷词语的使用变得肤浅表面,即使是夏威夷人也分不清什么才是正统的夏威夷文化。”

在全球化之下,每一种文化的交融都一样。在Hina身上可以看到中国、夏威夷与西方文化之间没有必然的冲突与隔阂,彼此共存。Hina说自己并不是反对美国或者西方文化,但是她确实非常热爱和支持夏威夷的传统文化。

电影结束之际,有观众问她能否给中国的LGBT群体说几句。她礼貌地反驳道,“与其到西方取经,倒不如在自己的文化里寻找答案?”或许,LGBT的问题古 已有之,还有许多在文明进程中由于不理解而出现的文化冲突,问题的答案往往就在我们自己的传统文化里。“简而言之,尊重自己丰富的文化传统,自信地面对外 来的文化统治者”。这就是真正的Aloha精神:爱、包容与尊重的别样传承。 -

Kumu Hina Gives Hope for the Future -- City Newspaper, Rochester, NY

- Posted on 9th Oct

- Category: news

by Dayna Papaleo - City Newspaper, Rochester, NY - 10/8/14:

The perpetual news cycle means that every other day there seems to be a new sound bite in which some clueless lawmaker in an expensive suit weighs in on with whom Americans should be allowed to share their hearts and/or genitals. But movie theaters have long been refuges from all that outside noise, and at ImageOut: The Rochester Film & Video Festival, love inspires art, rather than uninformed opinion.

From Friday, October 10, to Sunday, October 19, ImageOut celebrates its 22nd year with 39 programs of features, documentaries, and short films about the lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender experience.

As we learned in ImageOut 2010’s screening of “Two Spirits,” many indigenous cultures not only accept but embrace the idea of a third sex, one that falls somewhere in between the usual two.

Through the stirring, powerful documentary "Kumu Hina," we come to know one such mahu, a transgender Hawaiian woman named Hina Wong-Kalu devoted to helping her fellow islanders preserve their shared history by teaching traditional music and dance.

Directors Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson also chronicle Wong-Kalu’s spare time as the newlywed acclimates to everyday life with a young Tongan husband whose apparent liberality is at odds with a few misogynistic old-world notions.

Watch for the scene stealing Ho’onani, a pint-sized tomboy mirror of her teacher whose preternatural wisdom gives hope for the future.

-

KUMU HINA Wins Best Documentary Award at Festival Venezolano de Cine de la Diversidad

- Posted on 5th Oct

- Category: news

-

"A Story of Deep Inner Grace and Uplifting Beauty in a Paradisiacal Land" -- ImageOut Film Festival

- Posted on 27th Sep

- Category: news

ImageOut Rochester Review by Jennifer Morgan:

The inspiring documentary, Kumu Hina, introduces us to Hina Wong-Kalu, a native Hawaiian transgender woman embracing her cultural heritage in contemporary Honolulu as a respected teacher (or “kumu”), an active cultural council member, and a newlywed.

A beautifully animated prologue by Jared Greenleaf introduces us to the māhū tradition, and directors Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson (ImageOut 2009’s Out in the Silence) offer insight into Hawaiian history and culture while integrating several facets of Hina’s life with the native dance and music so dear to her.

Among the students at the Hālau Lōkahi public charter school, where Hina teaches native Hawaiian studies, we meet Ho’onani, a young tomboy who longs to lead the boys’ hula troupe in her school’s end-of-year pageant.

The compassion, support, and gentle respect that Hina brings to her students are evident throughout the film, exposing an especially rich aspect of her life and gifts as a teacher.

On assignment as a traditional burial council member, Hina oversees the respectful handling and care of native burials that may be disturbed as work on a new rail system progresses. She carefully inspects the advancing excavation and liaises between the native council, foreman, and work crews.

We share Hina’s joyful reunion with Hema, a young Tongan from Fiji still adjusting to his new life in Hawaii, and as their marriage unfolds we witness the ups and downs that come with any relationship as it enters a new phase.

Striking a balance by living an authentic life in a paradisiacal land, Hina’s story is one of deep inner grace, uplifting beauty, and self-empowerment.

Without ignoring the differences between traditional and contemporary attitudes, she molds a life full of dignity, humility, and true inner joy.

-

Going Global with the True Meaning of Aloha -- China Screening Tour

- Posted on 8th Sep

- Category: news

Greetings Friends,

This week, we’re heading off to China for a series of KUMU HINA events organized by local activists seeking to advance the country’s emerging movement for understanding and acceptance of transgender and gender fluid people.

We’ll be visiting Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Beijing, where Hina’s presence at the screenings, and her desire to make deeper connections with her Chinese heritage, is sure to heighten the experience for audiences in powerfully moving ways.

As Hina put it: “My Chinese grandmother has been one of the greatest influences in my life. But I’ve never had a chance to visit her ancestral home. I hope our film tour will do honor to the family name, and help Chinese viewers understand and embrace a message from my other homeland, about the true meaning of aloha - love, honor, and respect for all.”

If you can’t make it to China with us, there are lots of other screenings coming up.You can check out the full list of events and get all the details on the screenings tab.

Here are a few of the highlights just in case you’re in the neighborhood:Sept. 12-Austin, TX; Sept. 12-Fargo, ND; Sept. 13-Beacon, NY; Sept. 17-Honolulu, HI; Sept. 19-Geneva, Switzerland; Sept. 20-Palm Springs, CA; Sept. 21-Chicago, IL; Sept. 25-Hagatna, Guam; Sept. 27-Eau Claire, WI; Oct. 3-Caracas, Venezuela; Oct. 4-Tampa, FL; Oct. 6-Oaxaca, Mexico; Oct. 9-Seattle, WA; Oct. 9-Rochester, NY; Oct. 18-Kyoto, Japan; Oct. 18-Hamburg, Germany; Oct. 21-Hannover, Germany; Oct. 25-Lewisburg, WV; Nov. 9-San Diego, CA; Nov. 9-Juarez, Mexico; Nov. 11-Los Angeles, CA; Nov. 22-Philadelphia, PA; Dec. 10-New York, NY

If you don’t see anything near you on this list, KUMU HINA will soon be available on GATHR, an awesome new theatrical-on-demand service that enables people to bring the movie that they want to see to a theater in their community.

In the meantime, we look forward to sharing these and other journeys with you as we work together toward some better world.

Thanks for staying tuned,

Joe Wilson & Dean Hamer

Co-Producers/Directors

-

Kumu Hina Wins Youth Jury Award at Rhode Island International Film Fest

- Posted on 13th Aug

- Category: news

See All 2014 RIIFF Award Winners HERE

-

KUMU HINA Wins Audience Choice Award at AAIFF 2014 New York

- Posted on 12th Aug

- Category: news

The 37th Asian American International Film Festival Announces the 2014 Award Recipients – see full list HERE.

-

"A Stunning Eye-Opener, A Filmic Encounter"

- Posted on 23rd Jul

- Category: news

Transformers: New Yorkʻs Asian American International Film Festival

Filmmaker Magazine by Howard Feinstein - July 23, 2014

Over the years, many New York-based media arts organizations and the film festivals they produce have folded, or scraped by in spite of outdated approaches and rigid programming. Asian CineVision and its offspring, the Asian American International Film Festival, on the other hand, have proven to be the little engines that could. The secret to their success: a keen awareness of shifts in the zeitgeist and talent pool, without losing sight of the Asian American community they serve (with a value added outreach to non Asian American communities). They are masters of reinvention.

The 37th edition of the AAIFF (July 24-August 2) is comprised of 18 features and 33 shorts whose point of origin and makers might be Asian American or Asian (with an occasional non-Asian or non-Asian American directing an Asian subject).

One stunning eye-opener does not fit the usual fest slots: Kumu Hina, an intimate, very personal doc — a filmic encounter, really — by non-Asian American co-directors Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson (Out in the Silence). The two spent a year following a transgender woman, a mahu, someone who lies between male and female. In the context of this festival, she could, as a Hawaiian, be considered either Asian American or Polynesian, or both, because she is indigenous and closely identifies with her native culture.

Isn’t it ironic? A culturally specific subject plays a culturally pliant festival. The fact that the AAIFF begins on exactly the same day as Newfest this year (on a Thursday at that) makes it especially curious that Kumu Hina is screening at the Asian American rather than the LGBT fest. “Hina transcends the usual categories that western culture seems compelled to put people in,” says Hamer. “Some film festivals get that, like Frameline (where it won the Jury Prize for documentary). Others don’t, like Outfest and Newfest, which decided not to program the film, apparently because they had ‘too many trans docs’ this year — as if every film, too, had to be put in its own little box.”

Unlike what up until recently has been the fate of many transgender individuals on the mainland, Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, or Hina, lives in a supportive native Hawaiian culture that has traditionally held a respectful place for those whose sexual identities are outside the norm. (Jared Greenleaf’s powerful animation illustrates the pre-contact embrace of mahu.) She is a strong woman, the recent bride of a Tongan husband, and a successful teacher of arts, particularly dance, whose self-appointed mission is to promote native culture. She takes under her wing at Halau Lokali, a charter school geared toward all things native, Ho’onani, a young sixth-grade girl with strong ku, or energy, which puts the self-assured youngster in the middle, as they say in Hawaii, and enables her, with Hina’s blessing, to lead the boys-only hula class. (Hamer and Wilson’s next project is a short educational film on Ho’onani, told from her pov, with the goal of showing it in schools all across the country.)

The world Hina lives in, and by this I mean class as well as gender, is something that tourists never see. Here’s your chance — and a colorful world it is.

-

Trans Cinema is Here and Now

- Posted on 17th Jul

- Category: news

It’s about time that a multifaceted and diverse representation of trans themes, stories, and characters that mirror, validate, educate, and empower trans folks are being expressed and seen through the medium of film/media... READ COMPLETE STORY ON INDIEWIRE

-

Film on Spirit of Aloha Highlights Dallas Asian Film Fest

- Posted on 11th Jul

- Category: news

Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson didn’t start out as filmmakers, but they certainly have made an impact in the field.

They made their first documentary, the Emmy Award-winning Out in the Silence, after they got married in Vancouver and placed a wedding announcement in Wilson’s small-town newspaper of Oil City, Penn.

“For a year, the paper was deluged with a contentious, often ugly, debate about the ‘appropriateness’ of publishing a ‘gay’ wedding announcement in the paper,” Wilson says.

When they received a letter from the mother of a gay teen in Oil City whose gay son was being tormented at school, they filmed their PBS documentary about “the quest for fairness and equality for LGBT people in rural and small-town America,” Wilson says.

Their new documentary, Kumu Hina — which plays Saturday at the Asian Film Festival of Dallas — follows Hina Wong-Kalu, a native mahu (roughly, “transgender”) who strives to preserve Hawaiian culture in an increasingly Westernized world. We see Hina relate to her students (whom she teaches traditions such as hula), her husband (a Tongan struggling in the big city) and as a leader of cultural preservation.

We spoke with Wilson about this film, including the more enlightened approach to gender diversity in indigenous peoples and the need to connect with ancient cultures.

To learn more about the filmmakers’ grassroots campaign, visit Kickstarter.com and search “Kumu Hina: A Hawaiian Model for Gender Diversity.”

Dallas Voice: Hina is a strong woman and her students seem to respect her like a coach. Did any of them have any derisive things to say about mahu? How accepted is mahu among younger Hawaiians? Students in Hina’s school are very respectful. In Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander communities, mahu are a very visible and normal, part of everyday life — respected and included in family, school, church, business, community life, etc. It is only in the context of rigid Western thought, primarily religious, about gender that problems emerge. So, while negotiating daily life in modern Hawaii, mahu do encounter problems. But at Hina’s Hawaiian-values-based school, it’s not an issue. In fact, Hina is not the only teacher at the school who happens to be mahu.

In general, the Hawaiian spirit of aloha is very real. People here — Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike — tend to be much more courteous, respectful, welcoming and inclusive than in most other places. It’s simply a cultural way of life. If and when there is resistance in the day-to-day, it tends to be subtle rather than confrontational, which is why it didn’t emerge as a strong element in the film.

A right-wing religious and “family values” presence in Hawaii is on the increase, however, and with it is coming much more politicized and visible forms of bigotry and discrimination, as seen during last November’s special legislative session on marriage equality.

Is Hina’s story fairly typical of mahu today, or do many of them encounter more prejudice? Hina’s story is not necessarily typical, and she has experienced the challenges that many mahu and transgender women face in Hawaii’s heavily Westernized dominant culture, similar to trans women anywhere in the U.S. But, as she says in the film, Hina found refuge in being Hawaiian — Kanaka Maoli — and decided to share her story, and a glimpse of traditional Hawaiian cultureʻs more enlightened view of gender and sexuality, as a way to inspire hope for positive change in communities far and wide.

The young tomboy, Ho’onani, offers an interesting parallel story to Hina’s. Was that just luck? I’d love to follow her story 10 years from now. As portrayed in the film, Ho’onani emerged as a primary character in Hina’s story quite unexpectedly. But that is the magic of verite documentary filmmaking — you let the cameras roll and hope that you’re smart, or lucky, enough to capture compelling scenes. When Ho’onani appeared, wanting to join and ultimately lead the boys’ hula troupe, we knew we were witnessing something very special and just tried to make sure we were there to follow her and Hina on the journey they were taking together as mentor and [pupil] in unchartered waters.

While many who view the film are quick to put simplistic or convenient labels on Ho’onani, she is still on her journey, and we’ll see where it goes. The most important thing is that she, and other kids like her, have teachers, and other adults in their lives, like Hina who are willing and able to support them as they grow up and become who they want to be.

Is mahu the same as what we call “trans,” or is there some kind of subtle difference in the language? I love how Ho’onani defines it as “a rare person.” Mahu is a concept that refers more to those who embrace and embody both male and female spirit rather than those who simply transition from one gender to another. It is much more fluid and encompassing of a personʻs whole being rather than simply about biology and/or sex.

Mahu reminded me of the trans people in India who are respected insofar as it is “bad luck” not to give them alms, or Native Americans’ “third sex” who are respected as mystical. It seems many ancient cultures recognize a “third sex,” but many modern ones don’t. Yes, it seems that most indigenous cultures had and have ways of recognizing and honoring the diversity of the gender spectrum. So, our focus should not be to treat the concepts as exotic curiosities or relics of the past, but to counter the religious and other ideologically-driven institutions that have been trying to drive acceptance of gender diversity out of existence for centuries.

Hina and her husband Hema have a sometimes-contentious relationship, but I found Hema fascinating because he’s a simple, small-town farmer trying to be “modern” in his acceptance of a mahu as the woman he loves. Hema perhaps is a reflection of the younger generation of Polynesian men, struggling to make sense of all the conflicting things he’s been taught, including traditional Polynesian acceptance and his family’s conservative (Western) religious beliefs, grounded in a rigid interpretation of gender and sexuality. His journey in the film shows how he’s developing his own way of thinking about these things, aided greatly by a sense of openness and acceptance in Hawaii that he did not experience in his native Tonga. We hope his willingness to share his story in this film speaks to others in a similar spot in life and inspires them to be more independent in their thinking as well.

The hula and music/dance performances were so fascinating and contextual. Is that kind of native Hawaiian culture threatened today? The presence of Hawaiian culture, language and practices is strong in the islands, but also constantly under threat in a modern world more focused on commercial development and tourism than authentic cultural preservation and empowerment. Hina has become a very important figure in today’s Hawaii because she works so hard to keep Hawaiian culture and traditions alive, including the traditional embrace of mahu and others so commonly marginalized in Western society.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition July 11, 2014.