-

"Kumu In The Middle" - Hana Hou! The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines

- Posted on 16th Feb

- Category: news

By Chad Blair for Hana Hou! The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines

There’s a scene in the film Kumu Hina in which the hula teacher at Halau Lokahi stands facing six boys slouching in a doorway of the public charter school in Honolulu. The tattooed, five-foot-ten-inch-tall kumu (teacher) looks imposing despite the yellow plumeria tucked behind her ear. “Stand up straight. Stand tall,” she commands. She demonstrates: shoulders back, feet rooted. “I need this. This is what I need from you, all the time.” The boys comply, looking uncomfortable. Once the kumu is satisfied, she invites them to enter and sit before her. She belts the opening line of a chant from Hawai‘i Island hula teachers: “‘Ai ka mumu keke pahoehoe ke!” Her voice resounds in the huge space as she waits for them to repeat it.

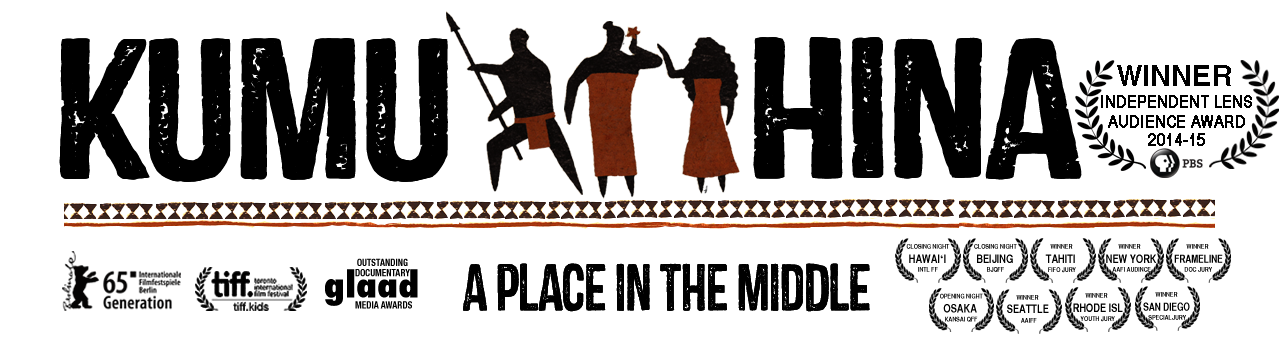

It’s all in a day’s work for any kumu trying to whip a group of hula-challenged high school boys into performance-ready shape. Forty-two-year-old Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu is a kumu hula, cultural practitioner and activist; the acclaimed documentary film based on her life premiered in April 2014 at Hawaii Theatre and has been shown on the Mainland and in Asia. It will be featured at the Pacific International Film Festival in Tahiti this February and air nationally in the United States on PBS in May. Kumu Hina is a portrait of a respected cultural practitioner passing Native Hawaiian values to her students. It is a love story, too, between Hina and her Tongan husband. More than anything it is the story of what it means to be mahu.

Kumu Hina has a long way to go with these boys. They try sheepishly to imitate her chant, their voices weak. Hina gently mocks them by whispering back: “‘Ai ka mumu keke …? No. Listen to my voice. There’s nothing wahine [female] about my voice. It’s thick and it’s too low.” She clears her throat, then chants the phrase again, deeper, louder and with almost physical force. The boys laugh, embarrassed and unnerved. Then she addresses them seriously, directly. “When I am in front of the entire school,” she intones, “you guys know that I expose my life. What the younger kids think about me, that’s up to them. But you, as older people, know.” What the boys know—and accept without question—is that their kumu was born male. “Now you, gentlemen,” says Kumu Hina, “gotta get over your inhibitions.”

Before the arrival of American missionaries in 1820, Hina explains in the film, every gender—male, female, mahu —had a role. Native Hawaiians believed that every person possessed both feminine and masculine qualities, and the Hawaiians embraced both, regardless of the body into which a person was born. Those in the middle—mahu—were thought to possess great mana, or spiritual power, and they were venerated as healers and carriers of tradition in ancient Polynesia. “We passed on sacred knowledge from one generation to the next through hula, chant and other forms of wisdom,” Hina narrates. After contact with the West, however, the missionaries “were shocked and infuriated. … They condemned our hula and chants as immoral, they outlawed our language and they imposed their religious strictures across our lands. But we Hawaiians are a steadfast and resilient people. … We are still here.”

From an early age Collin Kwai Kong Wong knew he was “different,” as Hina puts it now. “I wanted to be as beautiful and glamorous and smart as my mother. I wanted to be this beautiful woman. When my mother would go to work and leave me at home alone, I was in her closet.” Hina laughs recalling this, but it was hardly funny when it was happening: Collin was teased for being too feminine, and he didn’t know how to talk to his family about what he was going through. He tried, like others in such situations, to conform. “I had girlfriends when I was younger, and I tried to play the role,” Hina recalls. “I tried to be the person that I thought my friends and family were expecting to see.”

Collin learned Native Hawaiian values through his grandmother, but it wasn’t until he enrolled at Kamehameha Schools that he learned the practices: hula, oli and ‘olelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language). After graduating he worked as an assistant to a kumu hula and traveled throughout the Pacific to places like Tahiti and Rarotonga.

Back home in the Islands, he connected with Polynesians from other island groups, particularly those from Samoa and Tonga, among whom he felt more comfortable expressing his feminine side. “They had a more inclusive way about them,” Hina says. “It seemed easier to migrate toward transitioning into how my heart and spirit felt and know that there would still be a place for me. That I could be myself and people wouldn’t look at me with such scrutinizing eyes.”

Hina was delicate with her family as she began to transition at 20 years old, though her Hawaiian mother nonetheless struggled with it. “How did I transition from being my family’s son to being my family’s daughter? Not by throwing it in their face. Not by being militantly loud and obtrusive,” she says. Her Chinese father, perhaps ironically, was more accepting. “He said, ‘I don’t care what you do in your lifetime, just finish school and take care of your grandmother.’ He didn’t impose other things on me, and that said to me that my father would accept me unconditionally.”

Collin chose the name Hinaleimoana. Hina is the Hawaiian goddess of the moon, among the most desired figures in Polynesian mo‘olelo (stories), a name she says honors her mother’s cultural heritage and one that Hina hopes to “live up to.”

Hina had been teaching at Halau Lokahi for ten years when filmmakers Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer met her in 2011 through a mutual friend, Connie Florez, who became a co-producer of Kumu Hina. Wilson and Hamer were already known for their Emmy-winning 2009 film Out in the Silence, which chronicles Wilson and Hamer’s same-sex wedding and the uproar it subsequently caused in Wilson’s Rust Belt hometown of Oil City, Pennsylvania. Wilson and Hamer saw Hina’s story as a fresh approach to the topic. “As people who come from the continent, we often have a superficial understanding of Hawai‘i,” Wilson says. “Meeting Hina introduced us to a Hawai‘i that we might not otherwise know about. When she embraced us as filmmakers to document her story, we realized that this is a Hawai‘i that everybody needs to know about.”

That Hina was both respected and approachable was evident from their first meeting with her. “As we went to dinner at Kenny’s in Kalihi, just walking from the parking lot to the restaurant took about thirty minutes,” says Hamer. “There were so many people who knew her and came up to her. Coming from the Mainland, where a mahu might be looked at as suspicious, it was so different and wonderful to see her as part of her community.”

The crew shadowed Hina for two years and just let the cameras roll, often capturing touching moments between Hina and her students as well as a surprisingly intimate and honest view of her marriage. They filmed at Halau Lokahi, in her home and in Fiji. Much of the film focuses on Hina’s poignant relationship with a tough and talented middle school student, Ho‘onani Kamai, a girl who, like Hina, is “in the middle” and who, despite being female and considerably younger, confidently directs the high school boys as they practice their hula and leads them during the end-of-year performance. Wilson and Hamer are editing an age-appropriate version of the film that emphasizes Ho‘onani’s story to be shown in Hawai‘i schools. (The working title: A Place in the Middle.) “It’s told through the students’ point of view,” Wilson explains. “The value of that film is to reach people in the classroom setting.”

For her part, Hina says she is happy with the film and its success, though she insists that she didn’t do it for the stardom. “I don’t need the glory, I don’t need the fame,” she says, “but who doesn’t appreciate a pat on the back? What I want to know is that there is value and worth in my life—not the everyday value, but the larger value. Can I serve our people? Can I serve our community in ways big and small? I firmly believe that through being oneself, through living one’s truths and embracing one’s realities, others may find strength and courage.”

Not only are Hawaiians “still here,” as Hina says in the film, but once-suppressed native traditions like oli and hula are flourishing, and aikane (same-sex) marriages are today protected by Hawai‘i state law.

During the 2013 bill-signing ceremony for same-sex marriage in Hawai‘i, Kumu Hina delivered a stirring oli that sounded as if it roared from the caldera of Kilauea. She chanted before a packed auditorium of government officials, marriage equality advocates and friends and families at the Hawai‘i Convention Center. Those in the audience who did not understand Hawaiian wouldn’t know that Hina sang of “a new dawn.” But when Hina chanted about “the precious day of the aikane and of the mahu,” many in the audience laughed, clapped and whooped upon hearing the word “mahu,” causing the kumu herself to stop for a moment and break into a smile. (You can view the clip, with English subtitles, on YouTube.)

While she says she was honored to be asked by then-Governor Neil Abercrombie to deliver the oli, she did so “to be a catalyst for this change” and not, she says, to become a standard-bearer for LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) issues. That’s not a label, she says, that suits her; “I am not someone who wants to embrace LGBT and apply it to myself,” she says. Rather, it is her Hawaiian identity that predominates; if working in support of LGBT issues helps to serve that larger purpose, Hina is willing. But she points out that LGBT interests might well be served indirectly. “I put my-self out there for the larger community,” she says, “and if I do good for the larger community, then a more positive light will be cast on people like me.”

Last fall Hina concluded thirteen years as cultural director at Halau Lokahi. She’s still considering what she’ll do next, but whatever it is, it’s likely that she will advocate on behalf of Native Hawaiians. In 2014 she ran unsuccessfully for a position on the board of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Hina also chairs the O‘ahu Island Burial Council, which ensures that iwi kupuna—the remains of Hawaiian ancestors—are treated properly when they are unearthed during construction projects. Jonathan Likeke Scheuer, who served as her vice chairman before his term ended last June, praises Hina’s ability to reach consensus between developers and descendants —no small accomplishment, he points out, given the intensity of the disputes that erupt over the treatment of iwi kupuna. “Her leadership comes from an absolutely culturally grounded place,” Scheuer says. “She is so comfortable in her own skin, in being the person she is. She embodies who she is in this wonderful way that is really the source of her power.”

“I really don’t know what’s in store,” Hina says at the end of the film, and though she’s referring specifically to her marriage, she might as well be talking about her life as a whole. “What I do know is that I’m fortunate to live in a place that allows me to love who I love. I can be whoever I want to be. That’s what I hope most to leave with my students: A genuine understanding of unconditional acceptance and respect. To me that’s the true meaning of aloha.”

-

Kumu Hina: Teaching Us All About Love and Acceptance

- Posted on 4th Feb

- Category: news

by Margo Seeto - The International Examiner:

In traditional Polynesian cultures, people who embraced the spirit of a third gender, who embraced a blend of the constructed notions of male and female, were accepted and even revered. Among the kanaka maoli—the Native Hawaiians—men who fluidly move between roles of male and female are known as mahu. Mahu were often guardians of traditional cultural practices, such as hula. However, the 18th century introduction of Western European cultures and religions brought disease and war, in addition to a clash of values that continues to this day. No longer was it OK for aikane, or men who loved other men, to freely express affection for one another. Western religion said it was wrong.

Fast forward to contemporary Hawai‘i, and mahu still feel the affects of this intolerance of a traditionally-accepted group of people. Those who choose not to hide their identities must constantly fight barriers in family life, school, the workplace and politics. Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, born male as Colin Wong, is one such example of a fierce mahu who decided to pursue a life that spoke to her true self. “My progression is simply indicative of me coming to a different understanding. It was my own process of self-decolonization,” said Wong-Kalu to the International Examiner. It’s this attitude that garnered the attention of accomplished filmmakers Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson of qWaves Films.

Through Honolulu-based film producer Connie M. Florez, Hamer and Wilson met Wong-Kalu and filmed her from 2011 to 2013 for a documentary titled Kumu Hina. “They came to me and said that my life was interesting. I said, ‘Oh I don’t think so,’” said Wong-Kalu modestly. But in being a true individual with unwavering principles, Wong-Kalu went on to share about the film, “I wanted people to focus on me and my name, Hina … I just wanted it to represent my life. I don’t want the emphasis to be placed on transgender, though it can show me having challenges sometimes.”

During this time, Wong-Kalu was the Director of Culture at Halau Lokahi Public Charter School. As a kumu, or teacher, of traditional Hawaiian cultural practices, Wong-Kalu was the bearer of culture, as well as a role model for her students. And as if almost meant for film, three major developments created a trifecta of stories for the documentary: Wong-Kalu’s background and continued journey to become herself, her mentorship of a young girl determined to join and lead an all-boys hula troupe, and Wong-Kalu’s new marriage to a young Tongan man, Haemaccelo Kalu. With a prolonged lens into one’s private life, Wong-Kalu’s answer to a question about the camera’s constant presence was, “I simply said to myself that I have to be as honest and myself as possible. So that way, I don’t have an affected kind of representation in the film.”

In the past year, the documentary Kumu Hina has played around the global film festival circuit, from the Pacific Islands to Scotland, to China. While grounded in Hawai‘i, the documentary’s universal message of overcoming adversity has resonated with audiences. “It’s been a very powerful film and very well received in the places that it shows. Many people come up and are very expressive and appreciative about bringing the story to the forefront,” says Wong-Kalu. And true to her continued journey to becoming herself and connecting with her genealogy, Wong-Kalu shared, “My most significant [film festival] trip was to China. I got a chance to connect with my family there.” She is of Hawaiian, Chinese, Portuguese, and English heritage, and can speak English, Hawaiian, Tongan, Samoan, and Tahitian. As a self-professed “fan of languages,” Wong-Kalu looks forward to one day learning Cantonese in order to further get closer to her Chinese heritage.

While the cameras stopped rolling in 2013, the chapters of this kumu’s amazing life continue to be written. Having left Halau Lokahi Public Charter School in November 2014 after more than a decade on staff, Wong-Kalu is now an independent consultant currently working as a Native Hawaiian cultural adviser to the development group Howard Hughes Corporation. “I’m much more confident now to sit at the table with men in business and politics. Those are the kinds of tables that I sit at now, where you don’t usually have transgenders,” said Wong-Kalu of her current position. When asked if she was still teaching, Wong-Kalu responded, “I don’t teach anymore. Well, I do—I teach adults.” Continuing to build bridges and encourage understanding between communities seems to be in Wong-Kalu’s blood.

As for her hopes for what audiences will take away from watching Kumu Hina, Wong-Kalu said at the end of the International Examiner’s interview, “I’d like them to have unconditional love and understanding and acceptance of people who are different. I’d like them to understand that there are different paradigms of life that can exist. All are acceptable. … To other transgenders out there, all they have to do is put their heart and soul into their mind, and go north toward it.”

Kumu Hina screens at Northwest Film Forum Screen 1 (large theater) on Saturday, February 14 at 3:00 p.m. and at Northwest Film Forum Screen 2 (small theater) on Sunday, February 15 at 6:00 p.m. Kumu Hina is preceded by the short films Intersections and To Sit with Her. For tickets and more information, click here.

-

"A Beautiful Look into Hawaiian Culture and Living Outside the Gender Binary" -- AfterEllen.com

- Posted on 30th Jan

- Category: news

by Miranda Meyer - AfterEllen - January, 30, 2015:

A Place in the Middle is a documentary short about a young Hawai’ian person growing up “in the middle” of the gender binary; about the reclamation and celebration of Hawai’ian culture; the wounds of colonialism; the bonds between students and teachers; about acceptance. It is as much the story of Kumu Hina, a teacher and cultural activist, as it is of Ho’onani Kamai, her 11-year-old student, and much of the emotion that pours through the screen emerges from the profound differences in the experiences of these two “middle people” growing up.

I want to say up front that it can be tempting to try to evaluate the concepts and statements made in the short on the basis of my own understanding of post-colonial life, or of how we usually talk about trans, genderqueer, genderfluid, or agender people in the mainland United States. But I am not Hawai’ian, and so I have chosen to discuss these concepts in the filmmakers’ terms, sometimes skipping terminology that feels more familiar or “appropriate” in the contexts I am used to. This may feel jarring at times (I struggled with wording a lot on this basis), and I hope I’ve managed to stick to their terms without hurting anyone here—if I messed up, I hope we can talk about it. Also, though Ho’onani’s gender identity is certainly not cis-female nor specifically transfeminine, she is consistently referred to by those around her using female pronouns and does not seem to object, so I will do the same here.

The film states its subject right at the start, informing us that “In the Hawaiian language, kāne means ‘male’ and wahine means ‘female.’ But ancient Hawaiians recognized that some people are not simply one or the other.” We then go immediately to Ho’onani, in a backwards cap, playing ukulele and narrating herself in a mixture of Hawai’ian and English words:

Sometimes Kumu says I have more kāne inside than most of the kāne. And some kāne have more wahine than the wahine. Some people don’t accept it, they tease about it, but—I don’t care. At all. Because I’m myself; other people are theirselves.

Already we know a lot about our protagonist! She is certainly aware andconscious of the ways her gender is unusual, and that others sometimesobject to this. Her gender is a topic she has thought about.But what is maybe more remarkable in her, to my eyes, is how self-possessed and articulate she is. This 11-year-old kid has more confidence and security in herself, pouring out of her every word and gesture, than most adults or kids I know, and seeing that in her affect immediately makes the viewer feel safe.

We are not going to watch terrible things happen to Ho’onani. It is obvious that she is loved by people who support her. This all happened within the first minute and already I felt like I was in a group hug.

We move quickly to Ho’onani’s school in Honolulu, where it’s immediately obvious that the support you intuit from her brief speech is real. Kumu Hina, her teacher, is passing out leis, declaring that yellow leis are for the boys; all the boys should be in yellow leis. Kumu then checks in with Ho’onani: “You’re happy? You’re in a boy lei.” And indeed she is. She considers the question for a second, looking over a boy in his boy lei next to her, then perks up with all the force of a great idea: “I wanna just wear both!” The girl on her other side (in her white lei) looks up with an expression like Ho’onani has just won the lottery or cracked the code of life. SHE GETS TWO LEIS, GUYS!!!

I can’t hear what she says next, but she turns to Ho’onani—presumably to express her congratulations—and Ho’onani makes all kinds of triumphant “nailed it” gestures. Without questioning it, Kumu brings her a white lei and puts it on her, saying to the room at large, “You get both, cause she’s both.”

Honestly, I would love to describe the entire film in such detail because everything is just so great, but that would be unwieldy and spoilery. But this sequence very much sets the tone: Ho’onani’s gender, her bothness, is supported by her teacher and accepted by her peers. This incident is in no way a big deal to anyone in the room (except perhaps Kumu, but more on her later). Not only is she accommodated by her school in her self-expression, she is actively supported in a way I wish so much every kid could be. She didn’t have to speak up to ask for another lei; she was asked what would make her happy, and given the time to consider it.

The narrative thread of A Place in the Middle is preparations for the end-of-year school hula performance. This story is interspersed with some beautiful animated sequences explaining briefly and clearly some aspects of traditional Hawai’ian culture and it’s suppression by US colonial authority, as well as Kumu’s perspective. (I wish there were gifs out there somewhere of these animations, as their fluid quality of motion is really arresting, but alas we will have to make do with screenshots.)

The animation introduces us to māhū, or people in the middle, who prior to the cultural destruction of colonization “embraced both the feminine and the masculine traits that are embodied within each and every one of us.” As will happen frequently in these animated sequences, there are small but significant choices in how to illustrate concepts that make an enormous difference. The māhū icon does not appear already demonstrating their status of “in the middle;” instead, they stand between a male and a female icon who respectively offer them a flower and a spear. That these symbols of gender expression are shared freely reinforces the message that māhū were supported by and integrated in their societies.

We learn about the traditional role of the māhū, who were “valued and respected as caretakers, healers, and teachers of ancient traditions,” as well as the Europeans’ rejection of their existence. (The animation, again making important choices, illustrates this in definite terms of Christian missionaries without the narration having to say so.)

This description of māhū’s place as transmitters of tradition is in some ways the real heart of the whole film, as it underlies Kumu Hina’s life mission and even young Ho’onani’s role in the school performance. Kumu, we learn, grew up in the middle but without the support her student has. She speaks about the gendered bullying she endured and how she found strength and solace in native Hawai’ian culture; how her life’s work is the responsibility of carrying on Hawai’ian identity and imparting it to the next generation. (The movie was her idea, which makes perfect sense.) She refers to her “transition” without going into any detail, though we see “the old me” perform a traditional song. The presentation of this fact of her life as significant but not lurid or needing explanation is deeply refreshing in a world where trans and genderqueer people are so often pushed to provide some kind of play-by-play of how their genders and bodies have changed and interacted over time.

Kumu is not the only one who feels strongly about Hawai’ian heritage, however. We meet Ho’onani’s mother, who wants her to learn Hawai’ian language and culture because she herself never had the chance. We watch the school’s principal implore the students not to take the instruction they get at school for granted, because earlier generations never had it. Everyone cries. Ho’onani cries, Kumu cries, the principal cries. I cry too. The offending teenage boys gather around Kumu Hina and hug her en masse.

Lest my slightly flippant description sound maudlin or in any way eyeroll-y, I promise you this is not how the scene goes down. This little film is absolutely bursting with sincerity. The wounds these older women feel are very real, and their students’ appreciation of that, when faced with it, is real too. Māhū, we were just told, were traditionally healers, and the entire enterprise of this school feels like a collective, cross-generational process of healing.

In a more intimate version of that same dynamic, we watch Kumu Hina let Ho’onani be in the high school boys’ dance, not the girls, and cast her as the leader of the number. We see teacher advise student that others in the future may expect her to “stand in the girls’ line” and that she may have to just roll with it while she’s still young. But “When you get to be my age,” Kumu tells her, “You’re not gonna have to move for anybody else.”

Concepts of gender and sex are treated throughout the film with a degree of easy fluidity I have rarely experienced. Even in spaces dedicated to discussion of cissexism and all its handmaidens, sometimes the laudable and important desire to unpack our assumptions and include everyone with our language leads to a granular hashing out of terms and categories that doesn’t afford the kind of comfort that is demonstrated and modeled here. (This is essential work that should by all means continue! It is just different from what is happening in the movie.) Please note that I don’t believe for a second that the adults involved have not thought long and hard about the subject. What I mean is that they are discussing it with their charges in such a way that it doesn’t feel, at least from this side of the screen, like it’s fraught or exhausting. Nor does it feel flippant or underserved. It feels like a world where gender is discussed calmly and kindly by authority figures and where there is room for everyone’s expression.

In the first rehearsal we see, Kumu informs the guys, “You have a biological wahine standing here in front of you because she has more kū [male energy] than everybody else around here.” (Ho’onani is thrilled with this.) “Even though she lacks the main essential parts of kū. [Ho’onani laughs.] But in her mind, and in her heart, she has kū.” The idea that genitals are “the main essential parts” of any gender is one that is generally very unwelcome with me, but I am in no position to police Kumu Hina’s language and you could not pay me to try; I wrote down these words as one of several examples of how gender is addressed over the course of the film.

Later, as the boys wait to go onstage, Kumu Hina will start to say that Ho’onani isn’t a boy, but—and the boys will say, “He is.” “He is.” “He is.” Those same dancers will still later declare that “she has more balls” than any of them. (TEENAGE BOYS SAID THIS ABOUT AN ELEVEN YEAR OLD GIRL WHO WAS PUT IN A LEADERSHIP POSITION OVER THEM, YOU GUYS! WHAT ALCHEMY IS THIS!!!) Her female classmates will say that she’s in the middle and that it’s not a big deal, including the information that she plays ukulele and sings—these are all just facts about her. Her mother accepts her gender expression but barely comments on it at all, focusing instead on love and family. These various statements do not necessarily match up with one another precisely in the way gender discussions I’m used to often try to pin down—note the pronoun changes at different moments—but that is never an issue. This is what I’m trying to get at with words like fluidity and comfort. Gender here is dynamic and individual, and given the room to be so.

Moreover, it seems that while Kumu and Ho’onani are both in the middle, they are not in the middle in the same way; this is never really an issue. No one tries to sort them into subtypes or distinguish between their assigned-at-birth genders. There is an underlying feeling of space in terms of letting people be that permeates everything that happens here, but that space is never taken for granted. A Place in the Middle makes sure you can’t finish it without understanding that that place has had to be fought for and reclaimed, and that it cannot be found everywhere.

In the end, the performance goes beautifully. Ho’onani, dressed differently from the guys but standing front and center, opens her mouth and chants in a voice of such strength and depth that it’s nothing short of inspiring, and the crowd screams in joyous welcome. Her mother tells her over and over that she is proud. I cry some more.

At one point, Kumu Hina tells the group that she wants everyone to know that “if you are my student, you have a place to be.” “In the middle,” Ho’onani interjects. “In the middle! In the middle,” Kumu agrees. As Ho’onani’s mother said earlier, love means letting people be who they are, embracing them for who they are. A Place in the Middle tells us more than once about the true meaning of aloha: love, harmony. In this story, aloha means standing in the girls’ line or the boys’—or out in front, with two leis; different, but not alone.

Kumu Hina: A Place in the Middle will play at the Berlinale Film Festival, and will be available to educators and communities who would like to show the film. For more information, visit aplaceinthemiddle.org

-

'Kumu Hina: A Place in the Middle' Premieres at the 65th Berlinale

- Posted on 17th Jan

- Category: news

Jan. 17, 2015:

Produced & Directed by O'ahu residents Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson in association with Pacific Islanders in Communications, the film tells the story of a young girl who aspires to lead her school's all-male hula troupe and a teacher who uses Hawaiian culture to empower her.

“A true life Whale Rider!” -Huffington Post

January 20, 2015 – (Haleiwa, HI) – KUMU HINA: A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE is one of 65 films from 35 countries selected for the 65th Berlinale's Generation programme, a slate of state-of-the-art world cinema devoted to children and young people seen by more than 60,000 attendees annually.

Firmly grounded in their respective cultural contexts, the selected films paint sensitive portraits of extraordinary characters often living in hermetically sealed worlds. “We experience young people who bear too much weight on their shoulders,” as section head Maryanne Redpath describes one of this year's recurring themes. “The high degree of self-determination with which these children and adolescents liberate themselves from their predicaments is striking.”

A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE is the educational version of Hamer and Wilson's feature documentary KUMU HINA, which was the Closing Night Feature in the Hawai'i International Film Festival's 2014 Spring Showcase. The film has traveled the world for festival, campus, and community screenings, and will have its national PBS broadcast on Independent Lens on May 4, 2015.

In A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE, eleven year-old Ho'onani dreams of leading the hula troupe at her Honolulu middle school. The only trouble is that the troupe is just for boys. She's fortunate that her devoted teacher, Kumu Hina Wong-Kalu, understands first-hand what it means to be 'in the middle' – embracing both male and female spirit. Together, as they prepare for a big year-end public performance, student and teacher reveal that what matters most is what's in one's heart.

With nearly 500,000 visitors each year, the Berlinale is the largest publicly attended film festival in the world. A PLACE IN THE MIDDLE was one of over 5,000 submissions to the festival this year, and the only selection from Hawai‘i.

“An inspiring coming-of-age story on the power of culture to shape identity, personal agency, and community cohesion, from a young person's point-of-view.” -Cara Mertes, Ford Foundation's JustFilms

“I know that this film will bring understanding and enlightenment to all who view it.”

-Leanne Ferrer, Pacific Islanders in Communications

Festival info: Berlinale 2015

Film web site: http://aplaceinthemiddle.org/

-

"Hiding in Plain Sight: The Beijing Queer Film Festival" -- Filmmaker Magazine

- Posted on 7th Jan

- Category: news

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Beijing Queer Film Festival

by Dean Hamer - January 7, 2015:

My usual questions as I get ready for a film festival are whether we’ll be able to sell out the show and how the audience and local press will react. Preparing for the Beijing Queer Film Festival last September, I had a different sort of concern: would I be able to show our film without being arrested?

The festival had invited me, my partner Joe Wilson and our main character, Hina Wong-Kalu, to screen Kumu Hina, a documentary about Hina’s life as a highly regarded native Hawaiian teacher and cultural leader who just happens to be māhū, or transgender. Because China has a censorship law that prohibits any positive depiction of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender lives in movies or TV shows, mainstream venues were out of the question; the big international festivals in Shanghai and Beijing are devoid of gay-themed films, and DVDs of Brokeback Mountain are only available on the black market.

Which is exactly why the very existence of the Beijing Queer Film Festival is both so necessary and so audacious. Founded in 2001 by openly gay filmmaker Cui Zi’en, the early years were difficult. Screenings were cancelled by the security police at the last minute, films were moved from theaters and universities to bars and private homes, publicity was largely by word of mouth and organizers were threatened.

Then in 2013, for the first time, the festival went off without a hitch. Buoyed by the lack of governmental interference, the organizers for the 2014 edition decided to open up the festival by holding the screenings in a public cinema and marketing to the large Beijing LGBT community through social media.

Their timing was unfortunate. Last year was tough on progressive causes in China, as President Xi Jinping led a series of crackdowns on independent voices, arresting critics and shuttering NGOs. The most troubling was the brutal shutdown of the Beijing Independent Film Festival in late August. Authorities forcibly dispersed would-be audience members, shut off the venue’s electricity, and detained the organizers, seizing documents and precious film archives from their offices.

The Queer Film Festival organizers quickly recalibrated their approach, abandoning the idea of using a public cinema and cutting back on their social media activities. But the police were watching. Just weeks before the festival, two security officers paid a visit to festival co-director Jenny Man Wu — a young straight woman with a passion for queer cinema.

“We’ve tapped your phone and read all your emails,” they told her, “and if you go ahead with the festival as planned, there will be trouble.” These are not good words to hear out of the mouth of a Chinese policeman.

But LGBT Chinese are, by necessity, as resourceful as they are resilient. Shortly after arriving in Beijing, on the day before the opening of the festival, we received an email from an unfamiliar address telling us there was a new plan. We were instructed to go to the central Beijing railway station the next morning, purchase tickets for the 11:15 AM train to a town near the Great Wall, and proceed to car number 7. “Make sure to bring your laptops,” the note ended.

And so the next morning we found ourselves in a commuter train car filled with a colorful mixture of Chinese queer film buffs, filmmakers, academics, artists and activists. The organizers handed out flash drives containing the opening film, Our Story, an artful retrospective of the festival’s history. We counted down in unison, “san, er, yi”, then started our media players together. The Beijing Queer Film Festival was underway.

The rest of the festival went off without major incident. Most of the films were from China, which despite the pressure from the authorities has a growing gay indie movement, others from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea and Europe. There were features, documentaries, a variety of shorts including several student films, and panels on topics ranging from “Light Documentary, Heavy Activism” to “Women on Top.” Most of the screenings and panel discussions took place at the Dutch Embassy, beyond the purview of the Chinese authorities.

Kumu Hina, the closing night film, was screened in the basement of a nondescript building housing several NGOs. Despite its location in an obscure hutong, or old alley district, the room was packed and the reception ecstatic. There was even some press, which led to a feature article in “Modern Weekly” on Hina’s experience, as a person of mixed Hawaiian and Chinese descent, visiting the homeland of her father’s side of the family for the first time.

In the USA, many LGBT film festivals are struggling as queer movies become readily available in mainstream theaters and on TV and the web. For Joe and me, what made the Beijing screening among the most moving and memorable experiences we’ve had on the festival circuit was the realization that it was more than an entertainment, it was a statement. Every single person in the room was risking something – perhaps even their own freedom – just to be there. It was a rare opportunity to see how a community under duress depends on the power of film and storytelling to help bring about change.

-

"Hiding in Plain Sight: 'Kumu Hina' at the Beijing Queer Film Festival"

- Posted on 7th Jan

- Category: news

by Dean Hamer for Filmmaker Magazine, Jan. 7, 2015:

My usual questions as I get ready for a film festival are whether we’ll be able to sell out the show and how the audience and local press will react. Preparing for the Beijing Queer Film Festival last September, I had a different sort of concern: would I be able to show our film without being arrested?

The festival had invited me, my partner Joe Wilson and our main character, Hina Wong-Kalu, to screen Kumu Hina, a documentary about Hina’s life as a highly regarded native Hawaiian teacher and cultural leader who just happens to be māhū, or transgender. Because China has a censorship law that prohibits any positive depiction of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender lives in movies or TV shows, mainstream venues were out of the question; the big international festivals in Shanghai and Beijing are devoid of gay-themed films, and DVDs of Brokeback Mountain are only available on the black market.

Which is exactly why the very existence of the Beijing Queer Film Festival is both so necessary and so audacious. Founded in 2001 by openly gay filmmaker Cui Zi’en, the early years were difficult. Screenings were cancelled by the security police at the last minute, films were moved from theaters and universities to bars and private homes, publicity was largely by word of mouth and organizers were threatened.

Then in 2013, for the first time, the festival went off without a hitch. Buoyed by the lack of governmental interference, the organizers for the 2014 edition decided to open up the festival by holding the screenings in a public cinema and marketing to the large Beijing LGBT community through social media.

Their timing was unfortunate. Last year was tough on progressive causes in China, as President Xi Jinping led a series of crackdowns on independent voices, arresting critics and shuttering NGOs. The most troubling was the brutal shutdown of the Beijing Independent Film Festival in late August. Authorities forcibly dispersed would-be audience members, shut off the venue’s electricity, and detained the organizers, seizing documents and precious film archives from their offices.

The Queer Film Festival organizers quickly recalibrated their approach, abandoning the idea of using a public cinema and cutting back on their social media activities. But the police were watching. Just weeks before the festival, two security officers paid a visit to festival co-director Jenny Man Wu — a young straight woman with a passion for queer cinema.

“We’ve tapped your phone and read all your emails,” they told her, “and if you go ahead with the festival as planned, there will be trouble.” These are not good words to hear out of the mouth of a Chinese policeman.

But LGBT Chinese are, by necessity, as resourceful as they are resilient. Shortly after arriving in Beijing, on the day before the opening of the festival, we received an email from an unfamiliar address telling us there was a new plan. We were instructed to go to the central Beijing railway station the next morning, purchase tickets for the 11:15 AM train to a town near the Great Wall, and proceed to car number 7. “Make sure to bring your laptops,” the note ended.

And so the next morning we found ourselves in a commuter train car filled with a colorful mixture of Chinese queer film buffs, filmmakers, academics, artists and activists. The organizers handed out flash drives containing the opening film, Our Story, an artful retrospective of the festival’s history. We counted down in unison, “san, er, yi”, then started our media players together. The Beijing Queer Film Festival was underway.

The rest of the festival went off without major incident. Most of the films were from China, which despite the pressure from the authorities has a growing gay indie movement, others from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea and Europe. There were features, documentaries, a variety of shorts including several student films, and panels on topics ranging from “Light Documentary, Heavy Activism” to “Women on Top.” Most of the screenings and panel discussions took place at the Dutch Embassy, beyond the purview of the Chinese authorities.

Kumu Hina, the closing night film, was screened in the basement of a nondescript building housing several NGOs. Despite its location in an obscure hutong, or old alley district, the room was packed and the reception ecstatic. There was even some press, which led to a feature article in “Modern Weekly” on Hina’s experience, as a person of mixed Hawaiian and Chinese descent, visiting the homeland of her father’s side of the family for the first time.

In the USA, many LGBT film festivals are struggling as queer movies become readily available in mainstream theaters and on TV and the web. For Joe and me, what made the Beijing screening among the most moving and memorable experiences we’ve had on the festival circuit was the realization that it was more than an entertainment, it was a statement. Every single person in the room was risking something – perhaps even their own freedom – just to be there. It was a rare opportunity to see how a community under duress depends on the power of film and storytelling to help bring about change.

-

An Evening with Kumu Hina at the Ford Foundation

- Posted on 24th Dec

- Category: news

By Cara Mertes, Roberta Uno, & Luna Yasui -- Ford Foundation:

As grant makers at the Ford Foundation, we’re accustomed to collaborating. Our initiatives—Advancing LGBT Rights, JustFilms, and Supporting Diverse Arts Spaces—not only intersect; they also reinforce each other. When we work together, we’re reminded that three voices can truly sing louder than just one—an idea that was exemplified at a recent film screening and live performance.

On December 10, the foundation hosted 2014’s final JustFilms Philanthropy New York screening and performance series, this time celebrating cultural icon Kumu Hina, a transgendered Native Hawaiian activist and teacher, and the subject of the evening’s film. After her beautiful chanted greeting (a Hawaiian oli), she was joined on stage by world-renowned Hawaiian musicians Keali'i Reichel and Shawn Pimental, whose music brought the refreshing trade winds of Hawaii to a cold New York evening. By the time Kumu Hina returned to perform a hula, the 300-strong audience had been transported to a world of grace, revelation, and aloha.

The performances were the perfect prelude to the screening of Kumu Hina. Directed by Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson, the film tells the inspiring story of Hina Wong-Kalu, also known as Kumu Hina. In high school, she was a young man named Colin Wong, who harnessed Hawaiian chant and dance to embrace his sexuality as a māhū, or transgender person. As an adult teacher, Kumu Hina supports a young girl student, Hoʻonani, as she fights to join the all-male hula troupe, pushing against the boundaries of conventional gender roles. Kumu Hina provides a holistic Native Hawaiian cultural context that affirms Hoʻonani as someone who is waena (between) and empowers her to move fluidly in her identity.

Kumu Hina’s story centers on the power of culture to shape identity, personal agency, and community cohesion. It transcends the cliché of a young person coming of age through dance, because it is grounded in a Pacific Islander value system that offers a fluid way of understanding and valuing identity—giving us all fresh ways to see each other with empathy. The film also points to Hawaii's leadership as the first state to have two official languages, English and ʻŌlelo Hawai'i; as an early proponent of gay marriage; and as a model for a polycultural America, where culture and values influence each other and move fluidly across boundaries rather than live side by side, or in a hierarchy, as separate entities. But ultimately what makes this film so memorable is that it allows audiences to experience the incredible journey of one person and her community, teaching people everywhere to see, appreciate, and truly embrace LGBT people.

This special event demonstrated how arts and culture, including film, dance, and music, serve as a central means of self-expression and political activism for LGBT people of color. They also exemplify how partnerships—those three voices singing as one—can help amplify a powerful story and support our grantees as they reach for a wider audience.

-

"KUMU HINA: A Powerful Portrait" -- by Basil Tsiokos of 'what (not) to doc'

- Posted on 13th Nov

- Category: news

All Things Documentary by Basil Tsiokos:

Coming to Los Angeles’ ArcLight Doc Series tonight, Monday, November 10: KUMU HINA

Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson’s portrait of a powerful Hawaiian transgender teacher debuted at the Hawaii International Film Festival in Honolulu this Spring. It went on to screen at Frameline, QDoc, Maui, Dallas Asian, NYC’s Asian American, San Diego Asian, Rhode Island, Docutah, and LGBT fests in Beijing, Chicago, Jakarta, Austin, Hong Kong, Minneapolis, Auckland, and Wellington, among several others.

Hamer and Wilson’s film follows the interconnected, parallel stories of Hina Wong-Kalu, who teaches traditional Hawaiian culture at a Honolulu school, and her student, Ho’onani, a sixth grade girl who is drawn to the boys’ hula troupe. Championing the Hawaiian conception of mahu – the coexistence of male and female spirit – Hina encourages Ho’onani’s pursuit, and her trust is borne out as the tomboy quickly emerges as a leader of the group. Outside of the school setting, Hina contends with relationship issues, as her younger Tongan husband exasperates her with his drinking and jealousy, while she also tries to balance her work to preserve traditional Hawaiian culture, investigating the disturbance of local burial sites. The filmmakers adroitly capture a strong yet vulnerable woman in a well-rounded manner too often missing from many profiles of transgender individuals that only focus on a singular aspect of their identity.

-

Kumu Hina at TEDxMaui: "He Inoa Mana (A Powerful Name)"

- Posted on 30th Oct

- Category: news

by TEDxMaui:

Kumu Hina, an educator, social and political activist, and Hawaiian cultural practitioner, shares her experience as a transgendered woman exploring her half Hawaiian, half Chinese ancestry. In her talk, she shares about a recent trip to China which unexpectedly connected her to her family there, and the realizations this new connection is bringing to her about the origins of identity.

Recorded at TEDxMaui 2014, held on September 28, 2014 at the Maui Arts & Cultural Center.

-

Kumu HIna Live Interview on Akakū Maui Media

- Posted on 10th Oct

- Category: news

Hina & co-director Dean Hamer bare (almost) everything in this behind-the-scenes VIDEO interview with Shaggy Jenkins of Akakū Maui Community Media: https://vimeo.com/108416307