"Kumu In The Middle" - Hana Hou! The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines

By Chad Blair for Hana Hou! The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines

There’s a scene in the film Kumu Hina in which the hula teacher at Halau Lokahi stands facing six boys slouching in a doorway of the public charter school in Honolulu. The tattooed, five-foot-ten-inch-tall kumu (teacher) looks imposing despite the yellow plumeria tucked behind her ear. “Stand up straight. Stand tall,” she commands. She demonstrates: shoulders back, feet rooted. “I need this. This is what I need from you, all the time.” The boys comply, looking uncomfortable. Once the kumu is satisfied, she invites them to enter and sit before her. She belts the opening line of a chant from Hawai‘i Island hula teachers: “‘Ai ka mumu keke pahoehoe ke!” Her voice resounds in the huge space as she waits for them to repeat it.

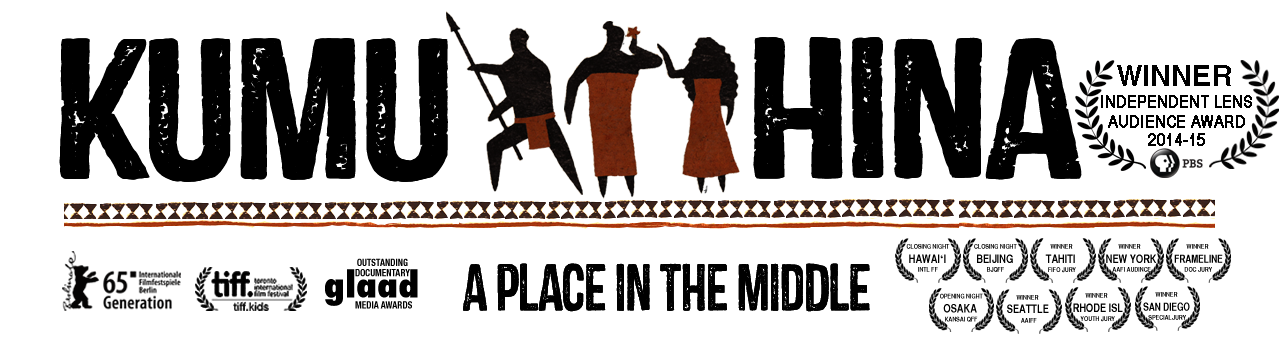

It’s all in a day’s work for any kumu trying to whip a group of hula-challenged high school boys into performance-ready shape. Forty-two-year-old Hinaleimoana Kwai Kong Wong-Kalu is a kumu hula, cultural practitioner and activist; the acclaimed documentary film based on her life premiered in April 2014 at Hawaii Theatre and has been shown on the Mainland and in Asia. It will be featured at the Pacific International Film Festival in Tahiti this February and air nationally in the United States on PBS in May. Kumu Hina is a portrait of a respected cultural practitioner passing Native Hawaiian values to her students. It is a love story, too, between Hina and her Tongan husband. More than anything it is the story of what it means to be mahu.

Kumu Hina has a long way to go with these boys. They try sheepishly to imitate her chant, their voices weak. Hina gently mocks them by whispering back: “‘Ai ka mumu keke …? No. Listen to my voice. There’s nothing wahine [female] about my voice. It’s thick and it’s too low.” She clears her throat, then chants the phrase again, deeper, louder and with almost physical force. The boys laugh, embarrassed and unnerved. Then she addresses them seriously, directly. “When I am in front of the entire school,” she intones, “you guys know that I expose my life. What the younger kids think about me, that’s up to them. But you, as older people, know.” What the boys know—and accept without question—is that their kumu was born male. “Now you, gentlemen,” says Kumu Hina, “gotta get over your inhibitions.”

Before the arrival of American missionaries in 1820, Hina explains in the film, every gender—male, female, mahu —had a role. Native Hawaiians believed that every person possessed both feminine and masculine qualities, and the Hawaiians embraced both, regardless of the body into which a person was born. Those in the middle—mahu—were thought to possess great mana, or spiritual power, and they were venerated as healers and carriers of tradition in ancient Polynesia. “We passed on sacred knowledge from one generation to the next through hula, chant and other forms of wisdom,” Hina narrates. After contact with the West, however, the missionaries “were shocked and infuriated. … They condemned our hula and chants as immoral, they outlawed our language and they imposed their religious strictures across our lands. But we Hawaiians are a steadfast and resilient people. … We are still here.”

From an early age Collin Kwai Kong Wong knew he was “different,” as Hina puts it now. “I wanted to be as beautiful and glamorous and smart as my mother. I wanted to be this beautiful woman. When my mother would go to work and leave me at home alone, I was in her closet.” Hina laughs recalling this, but it was hardly funny when it was happening: Collin was teased for being too feminine, and he didn’t know how to talk to his family about what he was going through. He tried, like others in such situations, to conform. “I had girlfriends when I was younger, and I tried to play the role,” Hina recalls. “I tried to be the person that I thought my friends and family were expecting to see.”

Collin learned Native Hawaiian values through his grandmother, but it wasn’t until he enrolled at Kamehameha Schools that he learned the practices: hula, oli and ‘olelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language). After graduating he worked as an assistant to a kumu hula and traveled throughout the Pacific to places like Tahiti and Rarotonga.

Back home in the Islands, he connected with Polynesians from other island groups, particularly those from Samoa and Tonga, among whom he felt more comfortable expressing his feminine side. “They had a more inclusive way about them,” Hina says. “It seemed easier to migrate toward transitioning into how my heart and spirit felt and know that there would still be a place for me. That I could be myself and people wouldn’t look at me with such scrutinizing eyes.”

Hina was delicate with her family as she began to transition at 20 years old, though her Hawaiian mother nonetheless struggled with it. “How did I transition from being my family’s son to being my family’s daughter? Not by throwing it in their face. Not by being militantly loud and obtrusive,” she says. Her Chinese father, perhaps ironically, was more accepting. “He said, ‘I don’t care what you do in your lifetime, just finish school and take care of your grandmother.’ He didn’t impose other things on me, and that said to me that my father would accept me unconditionally.”

Collin chose the name Hinaleimoana. Hina is the Hawaiian goddess of the moon, among the most desired figures in Polynesian mo‘olelo (stories), a name she says honors her mother’s cultural heritage and one that Hina hopes to “live up to.”

Hina had been teaching at Halau Lokahi for ten years when filmmakers Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer met her in 2011 through a mutual friend, Connie Florez, who became a co-producer of Kumu Hina. Wilson and Hamer were already known for their Emmy-winning 2009 film Out in the Silence, which chronicles Wilson and Hamer’s same-sex wedding and the uproar it subsequently caused in Wilson’s Rust Belt hometown of Oil City, Pennsylvania. Wilson and Hamer saw Hina’s story as a fresh approach to the topic. “As people who come from the continent, we often have a superficial understanding of Hawai‘i,” Wilson says. “Meeting Hina introduced us to a Hawai‘i that we might not otherwise know about. When she embraced us as filmmakers to document her story, we realized that this is a Hawai‘i that everybody needs to know about.”

That Hina was both respected and approachable was evident from their first meeting with her. “As we went to dinner at Kenny’s in Kalihi, just walking from the parking lot to the restaurant took about thirty minutes,” says Hamer. “There were so many people who knew her and came up to her. Coming from the Mainland, where a mahu might be looked at as suspicious, it was so different and wonderful to see her as part of her community.”

The crew shadowed Hina for two years and just let the cameras roll, often capturing touching moments between Hina and her students as well as a surprisingly intimate and honest view of her marriage. They filmed at Halau Lokahi, in her home and in Fiji. Much of the film focuses on Hina’s poignant relationship with a tough and talented middle school student, Ho‘onani Kamai, a girl who, like Hina, is “in the middle” and who, despite being female and considerably younger, confidently directs the high school boys as they practice their hula and leads them during the end-of-year performance. Wilson and Hamer are editing an age-appropriate version of the film that emphasizes Ho‘onani’s story to be shown in Hawai‘i schools. (The working title: A Place in the Middle.) “It’s told through the students’ point of view,” Wilson explains. “The value of that film is to reach people in the classroom setting.”

For her part, Hina says she is happy with the film and its success, though she insists that she didn’t do it for the stardom. “I don’t need the glory, I don’t need the fame,” she says, “but who doesn’t appreciate a pat on the back? What I want to know is that there is value and worth in my life—not the everyday value, but the larger value. Can I serve our people? Can I serve our community in ways big and small? I firmly believe that through being oneself, through living one’s truths and embracing one’s realities, others may find strength and courage.”

Not only are Hawaiians “still here,” as Hina says in the film, but once-suppressed native traditions like oli and hula are flourishing, and aikane (same-sex) marriages are today protected by Hawai‘i state law.

During the 2013 bill-signing ceremony for same-sex marriage in Hawai‘i, Kumu Hina delivered a stirring oli that sounded as if it roared from the caldera of Kilauea. She chanted before a packed auditorium of government officials, marriage equality advocates and friends and families at the Hawai‘i Convention Center. Those in the audience who did not understand Hawaiian wouldn’t know that Hina sang of “a new dawn.” But when Hina chanted about “the precious day of the aikane and of the mahu,” many in the audience laughed, clapped and whooped upon hearing the word “mahu,” causing the kumu herself to stop for a moment and break into a smile. (You can view the clip, with English subtitles, on YouTube.)

While she says she was honored to be asked by then-Governor Neil Abercrombie to deliver the oli, she did so “to be a catalyst for this change” and not, she says, to become a standard-bearer for LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) issues. That’s not a label, she says, that suits her; “I am not someone who wants to embrace LGBT and apply it to myself,” she says. Rather, it is her Hawaiian identity that predominates; if working in support of LGBT issues helps to serve that larger purpose, Hina is willing. But she points out that LGBT interests might well be served indirectly. “I put my-self out there for the larger community,” she says, “and if I do good for the larger community, then a more positive light will be cast on people like me.”

Last fall Hina concluded thirteen years as cultural director at Halau Lokahi. She’s still considering what she’ll do next, but whatever it is, it’s likely that she will advocate on behalf of Native Hawaiians. In 2014 she ran unsuccessfully for a position on the board of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Hina also chairs the O‘ahu Island Burial Council, which ensures that iwi kupuna—the remains of Hawaiian ancestors—are treated properly when they are unearthed during construction projects. Jonathan Likeke Scheuer, who served as her vice chairman before his term ended last June, praises Hina’s ability to reach consensus between developers and descendants —no small accomplishment, he points out, given the intensity of the disputes that erupt over the treatment of iwi kupuna. “Her leadership comes from an absolutely culturally grounded place,” Scheuer says. “She is so comfortable in her own skin, in being the person she is. She embodies who she is in this wonderful way that is really the source of her power.”

“I really don’t know what’s in store,” Hina says at the end of the film, and though she’s referring specifically to her marriage, she might as well be talking about her life as a whole. “What I do know is that I’m fortunate to live in a place that allows me to love who I love. I can be whoever I want to be. That’s what I hope most to leave with my students: A genuine understanding of unconditional acceptance and respect. To me that’s the true meaning of aloha.”

Leave a comment