-

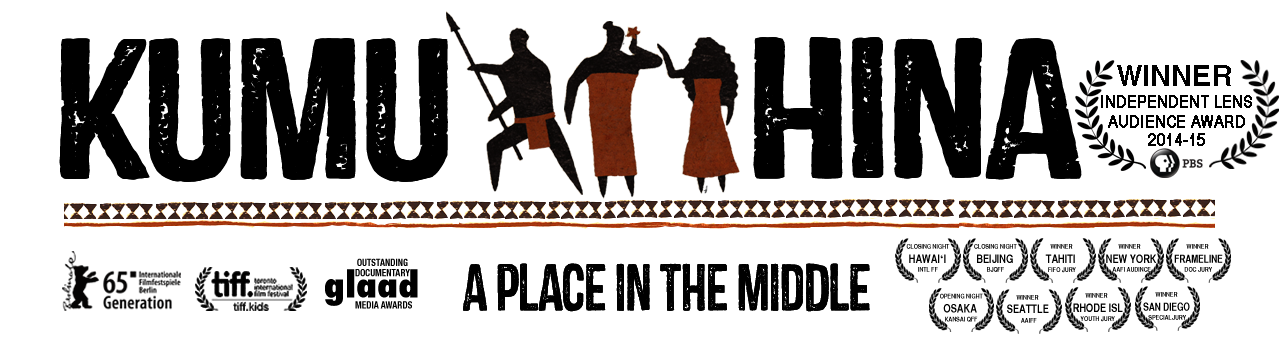

KUMU HINA Wins Frameline!

- Posted on 29th Jun

- Category: news

We are thrilled to announce that KUMU HINA has been awarded the Jury Prize for Achievement in Documentary at Frameline (Indiewire story). It's a great honor to be selected as the best documentary at "the largest, longest-lasting and most recognizable LGBT film festival in the work" - and even more amazing to receive a 5 minute standing ovation from 1400 fans at the historic Castro Theatre. Thank you Frameline!

-

"Native Hawaiian Refugee" - Bay Area Reporter Review

- Posted on 19th Jun

- Category: news

by Erin Blackwell - June 19, 2014:

No story of imperial conquest is pretty, but the corporate-Christian overthrow of the legitimate royal family of Hawai’i is among the most tragic, recent, and relevant to our lives. Ever eaten a slice of Dole pineapple or a cube of C & H sugar? There are so many terrible stories of Euro-American colonization it’s hard to keep up, but usurping this natural and cultural paradise as the 50th state is a heartbreaking model of greedy governmental treachery. The Frameline film Kumu Hina, screening Sun., June 22, at 3:30 p.m., fills in some gaps.

Kumu means teacher, and Hinaleimoana (“woman encircling ocean”) was the name chosen by Colin Wong as his female identity when he came out as a mahu. That’s a word impossible to translate because it’s charged with native cultural significance we mainlanders have no equivalent for, although Divine Hermaphrodite comes close. “People in the middle” is the expression used in the film, which traces a year in the life of Hina, cultural warrior doing daily battle for the promulgation of traditional hula, chant, and her non-biological right to dress as a woman and marry a man. In her words:

"A mahu is an individual that straddles somewhere in the middle of the male and female binary. It does not define their sexual preference or gender expression, because gender roles, gender expressions and sexual relationships have all been severely influenced by changing times. It is dynamic. It is like life.” She must mean the way I feel in the morning, deciding which flannel shirt to wear before I encounter the world and cringe inwardly when someone mistakes me for a man. A man is the last thing I want to be. But then, so is a woman .

Perhaps you intuitively understand mahu. Perhaps you’ve seen it at the opera. Kumu Hina is all about opera Hawai’ian style, the traditional hula and chant reenacting the myths and history of the Hawai’ian people. The film’s backbone is Hina’s labor of love imparting these ancient performing arts to kids and teens. There’s something tragic about Hina. There’s a gravitas you don’t get in Glee. She doesn’t teach show tunes or pop songs; her students dance and chant earth-rattling tributes to the volcano goddess Pele. They find their inner volcanoes by embodying rigorous traditional forms.

May the souls of the missionaries who suppressed the Hawai’ian religion burn forever in Hell. And that goes double for Dole. And throw in the British royal line.

Ho’onani, a tomboy in the sixth grade, is teacher’s pet. She not only gets to dance with the boys, she leads the chorus and is praised for her ku, or “male energy.” She looks a bit smug. I’m not sure all this indulgent praise isn’t going to her head, but she might need the experience of Hina’s unconditional love to call on in the years ahead. People can be so cruel to the ones in the middle. This sad truth is the film’s dark heart.

"It sucks to be a mahu sometimes,” Hina says during a fight with her new husband outside a parked Budget rental car beneath a beer billboard proclaiming “Enjoy the Moment” beside breeze-blown palm trees. They’re having what’s called a lover’s quarrel; the problem is Hema Kalu, 25, “can be an incredibly jealous Polynesian man sometimes.” He doesn’t consider himself gay. He thinks “a normal married woman doesn’t get calls from guys.” Seems like Hina loves a challenge.

"My husband is a full-on bushman," says Hina after we watch Hema and his pals roughly hog-tie a farm animal. "That’s part of the appeal." He’s also much younger, has a lovely falsetto, plays a mean ukulele, drinks kava and beer, and smokes more than is good for him. That’s hard to watch. This is not the Hawai’i of the tourist brochures. These are indigenous working-class people close to the land, struggling to make it in the city of Honolulu. Hema lands a job as security guard at Iolani Palace, but phones Hina for help when he misses the bus to work. That makes Hina a full-time teacher.

And teaching gives her strength. “In high school, I was teased and tormented for being too girlish,” she says. “I found refuge in being Hawai’ian. Being kanaka maoli [native]. My purpose in this lifetime is to pass on the true meaning of Aloha: Love, Honor, and Respect. It’s a responsibility I take very seriously.”

-

ʻKumu Hinaʻ Directors Interviewed on Radio New Zealand

- Posted on 11th Jun

- Category: news

"Of Both Male and Female Spirit"

The inspiring story of Hina Wong-Kalu, a transgender native Hawaiian teacher, as explored in the documentary Kumu Hina - with producers & directors Joe Wilson and Dean Hamer, interviewed by Bryan Crump.

Listen to the interview HERE. -

Kumu Hina: A Story of Triumph for All of Hawaii

- Posted on 10th Jun

- Category: news

by Trisha Kehaulani Watson:

My husband was Hina’s high school classmate and close friend. I have known Hina, considered her a dear friend, and loved her like family for years. The movie is actually the story of three people: Hina, a strong māhū Hawaiian; her husband Hema; and Ho’onani, one of Hina’s young students at Hālau Lokahi, a charter school in downtown Honolulu. Each undergo their own transition, and we are all witnesses to how their lives are transformed.

The movie Kumu Hina, produced and directed by Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson, captures these three critical stories as they unfold. Despite this multifaceted perspective, the core storyline belongs to Hina, a cultural champion in the Hawaiian community who has emerged from her struggled with her identity and become a powerful community leader. Her personal life journey involved far more than a transition from male to female - it is truly a story of becoming a powerful, confident Hawaiian māhū.

The film follows her as she travels to bring her Tongan husband home to Hawai’i from Fiji, where he has been staying as he awaited a visa to enter Hina’s home country. Despite the obvious love between the two, nothing about their relationship is easy. Perhaps it’s fair to say no relationship is easy, but the film illustrates that the challenges between Hina and Hema have little to do with her being māhū, and are more rooted in the cultural differences between the them.

The second story is Hema’s, who often seems overwhelmed by everything happening around him. It’s not difficult to imagine a sweet, genuine romance that takes place before the events of this film, but it’s clear that filming caught some of their more challenging moments. Hema is at times outright cruel and viciously disrespectful; it’s difficult to watch. It’s even more difficult to watch for those of us who know and love Hina.

The final and most poignant story belongs to Ho’onani, a young “tomboy” who confidently asserts her right to be part of the boys’ hālau (hula group), largely through Kumu Hina’s nurturing. This was my favorite storyline. It reflected a sort of closure for Hina, who was once a young student herself, picked on and harassed for her feminine ways in high school, yet grew to become a strong, inspiring teacher, fully capable of helping her own students. One can see that Ho’onani’s life has been significantly improved because of the obstacles that māhū like Hina have overcome, even if Ho’onani doesn’t fully comprehend the gravity of these triumphs yet.

There is one stairwell conversation between Kumu Hina and Ho’onani that is sure to make you ugly cry, and it’s my favorite scene of the movie. If that doesn’t get you, the scene of Hinaʻs students singing “Hawai’i Pono’ī” after being reminded that their forefathers could not, will have tears streaming down your face.

I wish the film had been longer, and elaborated more on different aspects of the characters’ lives. Furthermore, I wish it captured more of Hina’s stature in the Hawaiian community. She is a master of practice and language. She is a community leader and champion. She is stunning and glorious. These aspects of her persona should have taken center stage more often.

Hina transformed the role of māhū in Hawai’i. By asserting herself and using the powerful framework of Hawaiian culture, she continues to enforce the strength and importance of people whose identities cannot be defined by Westernized, cookie-cutter standards.

Ultimately, this film tells a story of love, transition and acceptance. In order to support those whom we love, we must be willing to bear witness to their struggles and triumphs, and understand their perspectives. Yet, beyond that, in order to be members of a community we must love and respect the beauty and power of every individual. We are all parts who make up a greater whole. I encourage everybody to watch this film, as it is a window into compassion and acceptance. It proves that those of us who may think we know the challenges faced by the māhū community still know very little. And we all have the power to change that.

As part of the 25th annual Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival, Kumu Hina will be screened on June 15 at 6:30 pm in the Doris Duke Theater at the Honolulu Museum of Art.