"Native Hawaiian Refugee" - Bay Area Reporter Review

by Erin Blackwell - June 19, 2014:

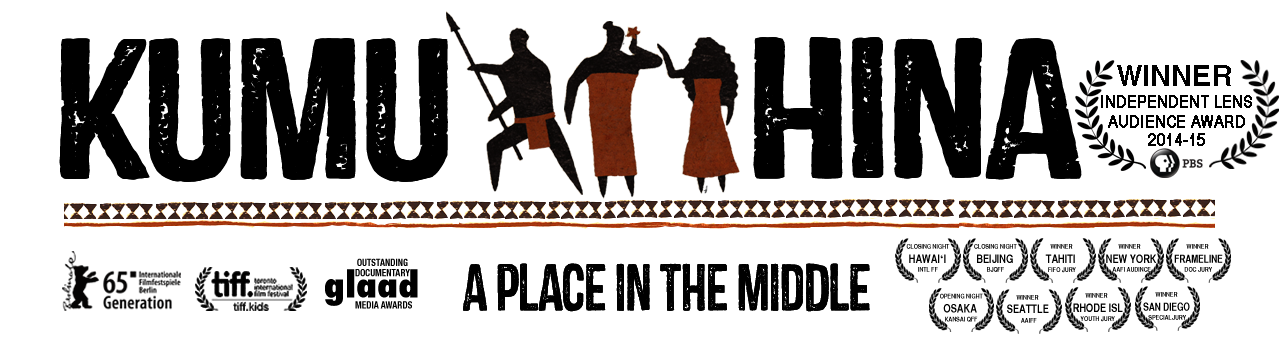

No story of imperial conquest is pretty, but the corporate-Christian overthrow of the legitimate royal family of Hawai’i is among the most tragic, recent, and relevant to our lives. Ever eaten a slice of Dole pineapple or a cube of C & H sugar? There are so many terrible stories of Euro-American colonization it’s hard to keep up, but usurping this natural and cultural paradise as the 50th state is a heartbreaking model of greedy governmental treachery. The Frameline film Kumu Hina, screening Sun., June 22, at 3:30 p.m., fills in some gaps.

Kumu means teacher, and Hinaleimoana (“woman encircling ocean”) was the name chosen by Colin Wong as his female identity when he came out as a mahu. That’s a word impossible to translate because it’s charged with native cultural significance we mainlanders have no equivalent for, although Divine Hermaphrodite comes close. “People in the middle” is the expression used in the film, which traces a year in the life of Hina, cultural warrior doing daily battle for the promulgation of traditional hula, chant, and her non-biological right to dress as a woman and marry a man. In her words:

"A mahu is an individual that straddles somewhere in the middle of the male and female binary. It does not define their sexual preference or gender expression, because gender roles, gender expressions and sexual relationships have all been severely influenced by changing times. It is dynamic. It is like life.” She must mean the way I feel in the morning, deciding which flannel shirt to wear before I encounter the world and cringe inwardly when someone mistakes me for a man. A man is the last thing I want to be. But then, so is a woman .

Perhaps you intuitively understand mahu. Perhaps you’ve seen it at the opera. Kumu Hina is all about opera Hawai’ian style, the traditional hula and chant reenacting the myths and history of the Hawai’ian people. The film’s backbone is Hina’s labor of love imparting these ancient performing arts to kids and teens. There’s something tragic about Hina. There’s a gravitas you don’t get in Glee. She doesn’t teach show tunes or pop songs; her students dance and chant earth-rattling tributes to the volcano goddess Pele. They find their inner volcanoes by embodying rigorous traditional forms.

May the souls of the missionaries who suppressed the Hawai’ian religion burn forever in Hell. And that goes double for Dole. And throw in the British royal line.

Ho’onani, a tomboy in the sixth grade, is teacher’s pet. She not only gets to dance with the boys, she leads the chorus and is praised for her ku, or “male energy.” She looks a bit smug. I’m not sure all this indulgent praise isn’t going to her head, but she might need the experience of Hina’s unconditional love to call on in the years ahead. People can be so cruel to the ones in the middle. This sad truth is the film’s dark heart.

"It sucks to be a mahu sometimes,” Hina says during a fight with her new husband outside a parked Budget rental car beneath a beer billboard proclaiming “Enjoy the Moment” beside breeze-blown palm trees. They’re having what’s called a lover’s quarrel; the problem is Hema Kalu, 25, “can be an incredibly jealous Polynesian man sometimes.” He doesn’t consider himself gay. He thinks “a normal married woman doesn’t get calls from guys.” Seems like Hina loves a challenge.

"My husband is a full-on bushman," says Hina after we watch Hema and his pals roughly hog-tie a farm animal. "That’s part of the appeal." He’s also much younger, has a lovely falsetto, plays a mean ukulele, drinks kava and beer, and smokes more than is good for him. That’s hard to watch. This is not the Hawai’i of the tourist brochures. These are indigenous working-class people close to the land, struggling to make it in the city of Honolulu. Hema lands a job as security guard at Iolani Palace, but phones Hina for help when he misses the bus to work. That makes Hina a full-time teacher.

And teaching gives her strength. “In high school, I was teased and tormented for being too girlish,” she says. “I found refuge in being Hawai’ian. Being kanaka maoli [native]. My purpose in this lifetime is to pass on the true meaning of Aloha: Love, Honor, and Respect. It’s a responsibility I take very seriously.”

Leave a comment