Film on Spirit of Aloha Highlights Dallas Asian Film Fest

Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson didn’t start out as filmmakers, but they certainly have made an impact in the field.

They made their first documentary, the Emmy Award-winning Out in the Silence, after they got married in Vancouver and placed a wedding announcement in Wilson’s small-town newspaper of Oil City, Penn.

“For a year, the paper was deluged with a contentious, often ugly, debate about the ‘appropriateness’ of publishing a ‘gay’ wedding announcement in the paper,” Wilson says.

When they received a letter from the mother of a gay teen in Oil City whose gay son was being tormented at school, they filmed their PBS documentary about “the quest for fairness and equality for LGBT people in rural and small-town America,” Wilson says.

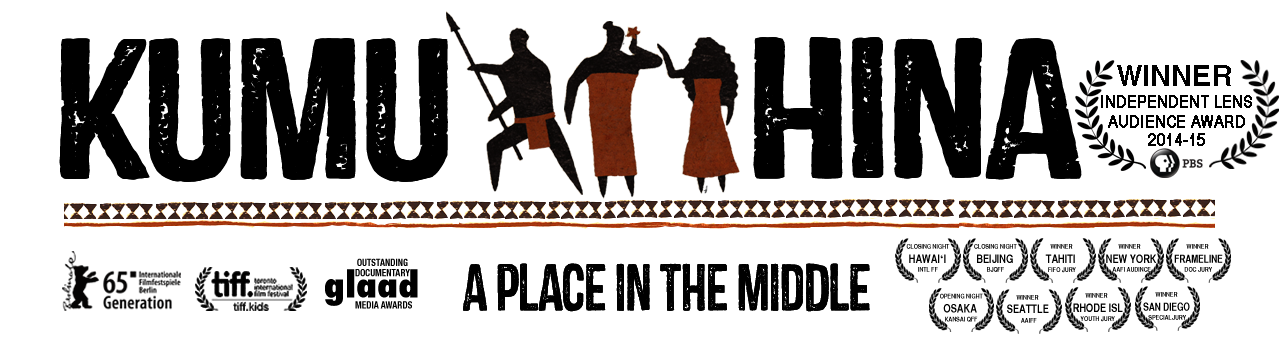

Their new documentary, Kumu Hina — which plays Saturday at the Asian Film Festival of Dallas — follows Hina Wong-Kalu, a native mahu (roughly, “transgender”) who strives to preserve Hawaiian culture in an increasingly Westernized world. We see Hina relate to her students (whom she teaches traditions such as hula), her husband (a Tongan struggling in the big city) and as a leader of cultural preservation.

We spoke with Wilson about this film, including the more enlightened approach to gender diversity in indigenous peoples and the need to connect with ancient cultures.

To learn more about the filmmakers’ grassroots campaign, visit Kickstarter.com and search “Kumu Hina: A Hawaiian Model for Gender Diversity.”

Dallas Voice: Hina is a strong woman and her students seem to respect her like a coach. Did any of them have any derisive things to say about mahu? How accepted is mahu among younger Hawaiians? Students in Hina’s school are very respectful. In Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander communities, mahu are a very visible and normal, part of everyday life — respected and included in family, school, church, business, community life, etc. It is only in the context of rigid Western thought, primarily religious, about gender that problems emerge. So, while negotiating daily life in modern Hawaii, mahu do encounter problems. But at Hina’s Hawaiian-values-based school, it’s not an issue. In fact, Hina is not the only teacher at the school who happens to be mahu.

In general, the Hawaiian spirit of aloha is very real. People here — Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike — tend to be much more courteous, respectful, welcoming and inclusive than in most other places. It’s simply a cultural way of life. If and when there is resistance in the day-to-day, it tends to be subtle rather than confrontational, which is why it didn’t emerge as a strong element in the film.

A right-wing religious and “family values” presence in Hawaii is on the increase, however, and with it is coming much more politicized and visible forms of bigotry and discrimination, as seen during last November’s special legislative session on marriage equality.

Is Hina’s story fairly typical of mahu today, or do many of them encounter more prejudice? Hina’s story is not necessarily typical, and she has experienced the challenges that many mahu and transgender women face in Hawaii’s heavily Westernized dominant culture, similar to trans women anywhere in the U.S. But, as she says in the film, Hina found refuge in being Hawaiian — Kanaka Maoli — and decided to share her story, and a glimpse of traditional Hawaiian cultureʻs more enlightened view of gender and sexuality, as a way to inspire hope for positive change in communities far and wide.

The young tomboy, Ho’onani, offers an interesting parallel story to Hina’s. Was that just luck? I’d love to follow her story 10 years from now. As portrayed in the film, Ho’onani emerged as a primary character in Hina’s story quite unexpectedly. But that is the magic of verite documentary filmmaking — you let the cameras roll and hope that you’re smart, or lucky, enough to capture compelling scenes. When Ho’onani appeared, wanting to join and ultimately lead the boys’ hula troupe, we knew we were witnessing something very special and just tried to make sure we were there to follow her and Hina on the journey they were taking together as mentor and [pupil] in unchartered waters.

While many who view the film are quick to put simplistic or convenient labels on Ho’onani, she is still on her journey, and we’ll see where it goes. The most important thing is that she, and other kids like her, have teachers, and other adults in their lives, like Hina who are willing and able to support them as they grow up and become who they want to be.

Is mahu the same as what we call “trans,” or is there some kind of subtle difference in the language? I love how Ho’onani defines it as “a rare person.” Mahu is a concept that refers more to those who embrace and embody both male and female spirit rather than those who simply transition from one gender to another. It is much more fluid and encompassing of a personʻs whole being rather than simply about biology and/or sex.

Mahu reminded me of the trans people in India who are respected insofar as it is “bad luck” not to give them alms, or Native Americans’ “third sex” who are respected as mystical. It seems many ancient cultures recognize a “third sex,” but many modern ones don’t. Yes, it seems that most indigenous cultures had and have ways of recognizing and honoring the diversity of the gender spectrum. So, our focus should not be to treat the concepts as exotic curiosities or relics of the past, but to counter the religious and other ideologically-driven institutions that have been trying to drive acceptance of gender diversity out of existence for centuries.

Hina and her husband Hema have a sometimes-contentious relationship, but I found Hema fascinating because he’s a simple, small-town farmer trying to be “modern” in his acceptance of a mahu as the woman he loves. Hema perhaps is a reflection of the younger generation of Polynesian men, struggling to make sense of all the conflicting things he’s been taught, including traditional Polynesian acceptance and his family’s conservative (Western) religious beliefs, grounded in a rigid interpretation of gender and sexuality. His journey in the film shows how he’s developing his own way of thinking about these things, aided greatly by a sense of openness and acceptance in Hawaii that he did not experience in his native Tonga. We hope his willingness to share his story in this film speaks to others in a similar spot in life and inspires them to be more independent in their thinking as well.

The hula and music/dance performances were so fascinating and contextual. Is that kind of native Hawaiian culture threatened today? The presence of Hawaiian culture, language and practices is strong in the islands, but also constantly under threat in a modern world more focused on commercial development and tourism than authentic cultural preservation and empowerment. Hina has become a very important figure in today’s Hawaii because she works so hard to keep Hawaiian culture and traditions alive, including the traditional embrace of mahu and others so commonly marginalized in Western society.

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition July 11, 2014.

Leave a comment