7 Essential Pacific Films to Add to Your Queue, from "Once Were Warriors" to "Kumu Hina" - Sundance Institute

By Kristian Fanene Schmidt - Sundance Institute - May 21, 2021:

In celebration of Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, it brings me great pleasure to highlight some of my favourite offerings when it comes to films from and/or about the Pacific. Before I do that, though, I think it’s important to give context around what constitutes a “Pacific Islander.”

Technically, the Pacific Islands consist of three regions: Micronesia (“small islands”), Melanesia (“islands of Black people”), and Polynesia (“many islands”). This was what I was taught growing up in Aotearoa, although the definition really depends on who you speak to and where they come from! Whatever definition you come across, we know that at the end of the day, race is a social construct. I created this video to describe how problematic these terms are in nature, which is often the case when they’re imposed by white men who “discovered” our lands and waters that were already inhabited for centuries.

Pacific Islanders are not a monolith. The same way the all-encompassing pan-Asian “Asian” identity lumps over 40 distinct cultures together, the “PI” part fails to capture the nuance of over 20 diverse nations. In using these labels, you often have voices from particular countries dominate discourse, while others get erased based on factors like population size, political power, and anti-Blackness.

In composing this list, I wanted to be very intentional in moving away from the usual Hollywood tropes, stereotypes, and one-dimensional narratives that sell in favor of amplifying lesser-known voices and issues to American audiences. OK! So now that we’ve covered that off, let’s get into it!

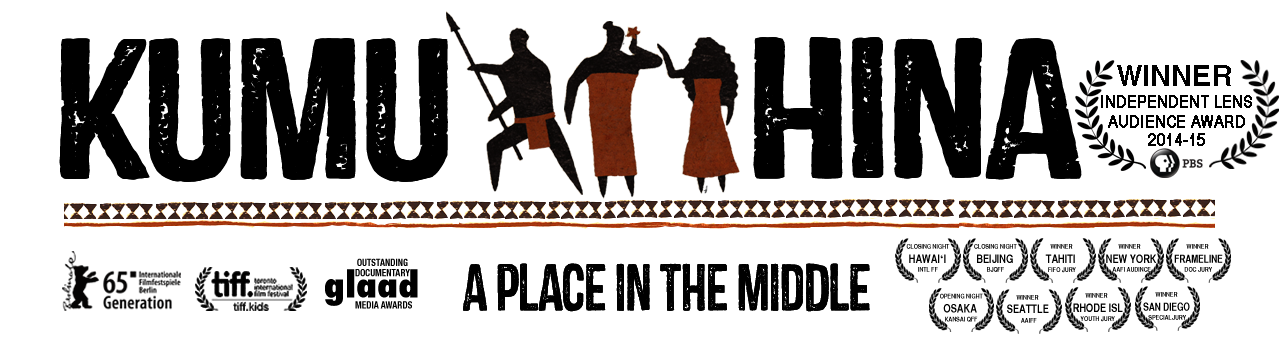

KUMU HINA (2014)

Kumu Hina follows the life of Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu, a Native Hawaiian activist and teacher. As a queer Samoan, I would be remiss not to include a narrative that speaks to the diversity in gender expression and sexuality in the Pacific that has long been demonized and outlawed because of the church and colonization. Hina is māhū, and while some māhū may identify as trans or nonbinary, I’m going to resist labelling her as such because not all do. (The trouble with using Western terms to describe Indigenous peoples is that they do not necessarily relate to them nor are they neat translations.) Navigating a world she seldom finds acceptance in, Hina is steeped firmly in her role as a cultural and spiritual leader, fighting for her people while holding true to who she is. We’re now starting to see a rise of queer Pacific content, as evidenced by another documentary made by the same creators, Leitis in Waiting, which is just as insightful. Hopefully there’ll be more to come.

NAMING NUMBER 2 (2008)

It’s rare for a Pacific playwright to have their works adapted into a feature film, let alone one that was written and directed by them! Naming Number 2 (known as No. 2 back home) by Fijian New Zealander Toa Fraser is a loving celebration of life centering a Fijian family living in the Auckland suburb of Mount Roskill. The story alone is beautifully told and boasts some wonderful talent, such as the late Ruby Dee — who Fraser sought out being a big fan of Do The Right Thing and her work in it — but I find the journey of the play to the big screen equally as impressive.

After selling off the rights to his theatrical debut, Bare, Fraser learned an important lesson, so when it came down to making 1999’s No. 2 into a movie, he made sure he was in a position to call the shots. Despite getting pushback for never having directed any projects, Fraser stuck to his guns, largely out of a responsibility to the Pacific community, and thankfully he did. Naming Number 2 went on to win the Audience Award: World Dramatic at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival, and Fraser’s been crazy busy in the U.S. ever since. I also recommend pre-colonial Māori action/adventure The Dead Lands, which feels like such a 180 in comparison but speaks to Fraser’s versatility.

ISLAND SOLDIER (2017)

While Island Soldier wasn’t directed by a Pacific Islander, it is an important documentary that gives viewers a reliable insight into the exploitative and destructive nature of U.S. militarism in the Pacific, specifically Kosrae in Micronesia. It’s becoming more and more common for this type of content to be what tips the scales in changing policy, so I encourage people to take the time and educate themselves by watching stories like this one and Anote’s Ark on climate change in Kiribati, as well as Ciara Lacy’s Out of State on addiction and incarceration in Hawai‘i, all of which share colonization and capitalism as the root of our problems. These are just some of our realities that don’t get the attention — and certainly not the reparation — they deserve.

VAI (2019)

Released in 2019, Vai is a beautiful collection of eight shorts spanning the Pacific, tied together by a common thread of mana wahine. What I love most about this film is that in addition to being directed by nine Pacific women, we get to see dark-skinned grandmas, mothers, daughters and sisters in such fullness and beauty, thanks to Solomon Islands filmmaker Matasila Freshwater and Fijian filmmakers the Whippy Sisters, respectively. Due to colorism that permeates every nation, Melanesians often get erased and excluded from Pacific discourse, so I’m looking forward to seeing more content like this and the Vanuatu love story Tanna! Vai is actually a follow-up to another great movie showcasing eight Māori women directors, Waru. Be sure to watch them together, and keep an eye out for a third installment with a focus on our Aboriginal whānau coming soon.

ONCE WERE WARRIORS (1994)

Arguably Aotearoa’s most well-known film, Once Were Warriors is based on Alan Duff’s novel of the same name, Lee Tamahori’s 1994 feature centers on the Heke family, a Māori whanau struggling with poverty, alcoholism, and domestic violence. Upon its release, it blew up in the media, who praised brilliant performances from Temuera Morrison, Rena Owen, and Cliff Curtis; critics at the time also noted its hauntingly realistic, visceral portrayals of both physical and sexual abuse. While it is definitely hard to watch in several moments, at the core of this tale is a need to return to Indigenous knowledge and practices for solutions and healing. Note that this is based on a confronting truth in Māori communities, but it’s only one truth: There are several others. To help avoid falling into the trap of ignorant preconceptions and prejudice, you can round things out by treating yourself to other gems like The Dark Horse, Whale Rider, Patu!, and Poi E.

WAIKIKI (2020)

You can spot Hawai‘i in countless television shows and movies, but Waikiki is the first feature film written and directed by a Native Hawaiian, Sundance Institute Native Lab alum Christopher Kahunahana. It’s something I definitely felt as I stayed captivated by its raw energy, stripped of all the routine glamour and tourist-trap illusions the world has come to associate with Hawai‘i. That’s Hollywood, but it’s not what the Indigenous are living! Danielle Zalopany is perfectly cast in her role as dancer Kea. As she fights for her survival and sanity, we get a real sense of the plight of kanaka māoli, but also where the true beauty and power of Hawai‘i lies — in the people, in the land, and in their connection to one another.

O LE TULAFALE (2011)

Tusi Tamasese’s 2011 feature O Le Tulafale (or The Orator) is Samoa’s first feature film that was written and directed by a Samoan, shot entirely in Samoa, in the Samoan language, with an all-Samoan cast. Whew! Saili (Fa'afiaula Sanote) is a taro farmer who faces constant ridicule and rejection in his village for being a little person. When his family and land comes under threat, Saili is the only one left to defend them. While the setting is very Samoan, the themes of adversity, love, and courage are universal. From the story to the cinematography to the performances, there’s a wholeness to it that makes me proud of it. I can confidently say it does justice to our people and our culture in representing fa‘a Samoa (the Samoan way) authentically and thoughtfully, warts and all.

Leave a comment