"Facebook Comments by Oregon City Councilor Highlight Fears of Coming Out" ~ East Oregonian

Facebook Comments by Oregon City Councilor Highlight Fears of Coming Out

By Jade McDowell – October 10, 2017

When filmmaker Joe Wilson, a gay man who makes documentaries about members of the LGBTQ community, began arguing with a man on Facebook about transgender discrimination, it was hardly his first time dealing with angry comments about gay and transgender people.

As the confrontation escalated, however, and Wilson clicked on the man’s profile, he was alarmed to see that the man he was arguing with — Lou Nakapalau — was an Echo, Oregon city councilor.

“When you croak of AIDS (Anally Injected Death Serum) I’ll spit on your grave queerbait,” Nakapalau wrote, adding the anti-gay slur.

As the LGBTQ community and their allies prepare to celebrate National Coming Out Day on Wednesday, Wilson said the fact that a city official would feel so comfortable saying things on a public Facebook page shows how much work remains to help people feel safe coming out as LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer).

“It’s taking a big step in life, if you know people have that kind of horrific and visceral reaction that can have very dangerous consequences,” he said.

It can set a tone for other people in a community to feel that they can echo their leaders, he said, or can make LGBTQ community members worry their leaders will set discriminatory policies or be prejudiced against them.

“If somebody is an elected official, it means they have a soapbox, a platform, to say things,” he said.

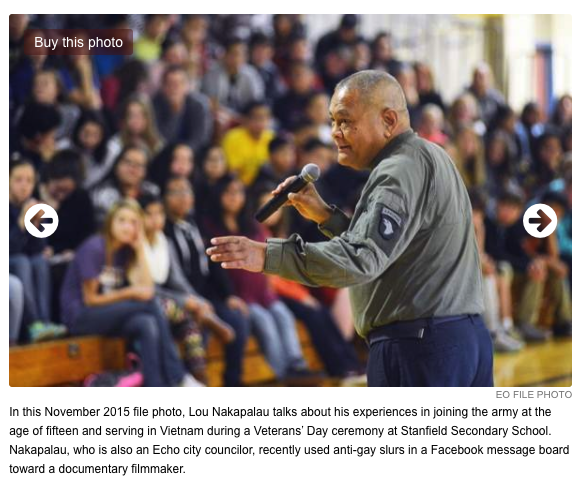

Nakapalau did not return a Facebook message, email or voicemail asking for comment, and Echo city administrator Diane Berry declined to comment. Nakapalau, a Vietnam war veteran, was sworn in as a new city councilor in January after receiving the most write-in votes for an uncontested seat in the town of about 700.

The exchange between Wilson, who lives in Hawaii, and Nakapalau happened on the “Kumu Hina” Facebook page, named after a documentary Wilson released in 2014 about a transgender Hawaiian woman. Wilson had posted an article about the Trump administration’s statement that transgender workers are not protected by federal anti-discrimination laws. Nakapalau commented that transgender people already have rights and he’s “Sick of the LBGTQ crowd shoving their ho keyed up agenda down my throat.”

Wilson responded by calling Nakapalau “sad” and said that the Confederate flag on his profile “says it all.” As the men continued to argue, Nakapalau called Wilson a profanity and said he has “relatives that are LBGTQ whom l love and I’ll defend them to my last breath” but didn’t want to be forced to support something he didn’t believe in, while Wilson accused Nakapalau of bigotry and said “no one is trying to shove anything down your throat, though your protests indicate that that is what you would likely most enjoy.” That’s when Nakapalau said he would spit on Wilson’s grave.

Wilson said his quip was trying to use “humor and mocking” to show the comments weren’t welcome. He said comments like Nakapalau’s, and silence from others in response, has a chilling effect on members of the LGBTQ community coming out. Wilson said the incident was especially jarring because in 2010 he visited nearby Hermiston and Pendleton to screen his film “Out In the Silence,” about the experience of being openly gay in a small, rural town.

Haley Talamontes knows what it’s like being gay in a small town. She said her experience living in Hermiston has included wonderful people, but also closed-minded people. A few years ago when she volunteered at a booth at the Umatilla County Fair for Umatilla Morrow Alternatives, a since-disbanded group that advocated for equality for minorities, she said a few people called her homophobic names in front of her children or told her she was “not right in the head.”

She said when she came out as a lesbian she finally felt truly free. But it didn’t come without consequences.

“You lose friends, you lose family,” she said. “My mom doesn’t talk to me.”

In November President Donald Trump told CBS he was “fine” with gay marriage, and years before becoming president indicated his support of the LGBTQ community numerous times, including a 2000 interview in which he said he would support adding sexual orientation to the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But some in his administration, including Vice President Mike Pence, have been vocal opponents of gay marriage, and since Trump became president his administration has announced a ban on transgender soldiers in the military and argued in court that federal law does not protect gay or transgender workers from discrimination by employers.

Talamontes said the Trump administration’s attitudes toward LGBTQ issues has caused some people to treat their sexual orientation more carefully, similar to undocumented immigrants who are now more careful about revealing their status.

That’s why she caused a scene at the doctor’s office the other day when the nurse insisted her 12-year-old daughter had to answer a question about her sexual orientation as part of a well child check-up. Talamontes said her daughter isn’t gay, but Talamontes worries for young people who are and may have parents who would kick them out of the house or abuse them if they found out.

She also worries that if she were the patient, answering the question truthfully could cause her problems later if she moved to a state with fewer anti-discrimination protections and any nurse or insurance agent could pull up that information.

Talamontes said she just wants to be loved and respected and not treated like she has some sort of “grotesque disease” that someone may catch from standing too close.

For

members of the LGBTQ community or their friends and family who are

looking for support, Pendleton has a chapter of PFLAG, short for

Parents, Family and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. They can be

contacted at 541-966-8414, pflag.pendleton.or@gmail.com

or

the PFLAG Pendleton Oregon Chapter Facebook page.

Leave a comment