On Cameron Croweʻs ʻAlohaʻ and Other, More Important, Indigenous Pacific Films

By Hinemoana of Turtle Island: Lani Teves, Liza Keanuenueokalani Williams, Maile Arvin, Fuifuilupe Niumetolu, Natalee Kēhaulani Bauer, and Kēhaulani Vaughn:

There’s been a lot of talk about the film Aloha. A standard Hollywood Romantic Comedy, Hawaiʻi, Hawaiians, ghosts, iwi (ancestral remains), and references to “mana” (power, supernatural power) are the backdrop for a settler colonial narrative that centers the U.S. military as a (fairly) benevolent presence that foregrounds a mundane story of boy meets girl; and boy gets redeemed by girl. The film itself is fairly nonsensical–a maze of tired plots that never resolve believably. Initially it seems the film is building towards the negotiation with a Kanaka Maoli community located in Waimānalo on the island of Oʻahu, regarding the removal of iwi and the blessing of a new pedestrian gate on the Hickam Air Force Base. (It is unclear why exactly a community in Waimānalo would be consulted for iwi at Hickam, on the other side of the island.) Yet, once the blessing is underway, the main characters are suddenly rushed off to a spontaneous, secret satellite launch (which Bradley Cooper’s character Brian Gilcrest must then blow up with sound waves because there are privately owned weapons hidden on it!).

The Hickam gate blessing, and the plot lines that center Kanaka Maoli negotiations with the U.S. military, are made complicated in the sense that real-life Maoli community leaders and activists perform roles in the film as themselves, engaging the cultural and activist work they do in life. The gate blessing and Gilcrest’s rogue actions to blow up the “evil” privatized satellite encapsulate the major problem with the film, as well as the major problem with many critiques of the film currently circulating. The U.S. military comes out as a naive and duped presence that, if it were not for Gilcrest’s rogue behavior, would have allowed the crazy shenanigans of an uber-rich individual to surpass U.S. military intelligence by sending weapons into space orbit. In this sense, the U.S. military, despite its illegal occupation of Hawaiʻi (which is referenced in the film), comes out innocent – and the “bad-guy” is simply a wayward individual with too much money on his hands. Further, the film makes the matter of the iwi removal and gate blessing seem as if it is a nice courtesy the military is extending (or a stunt they are pulling to have good public relations), when in fact the removal of iwi is protected by state law and managed by island burial councils.

Supposedly intending to be a film that really addresses authentic Hawaiʻi, the film literally rushes away from true respect or even engagement with Native Hawaiian culture, history and epistemology. The film is haunted with confusion, reflected in its inability to follow a through line in its overarching plot. More importantly though, the nonsensical plot lines may reveal deeper chasms between the American cultural imaginary and on-the-ground Kanaka Maoli politics. Attempting (and yet failing) to bridge the Hollywood imaginary with the complexity of lived life for Kānaka Maoli, ghosts (Night Marchers, a supernatural wind, and references to mana) emerge as the film’s only way of attempting to reconcile U.S. domination and histories of indigenous culturecide and dispossession in Hawaiʻi. In addition, the critiques of the film have remained superficial, failing to engage or respect Native Hawaiians, focusing instead on calls for Asian American actresses to replace Emma Stone.

Rather than critique the nuances of its storyline, we would like to engage what the film represents, and suggest alternative films and readings for those who are interested in responsibly engaging Native Hawaiians and other Indigenous Pacific Islanders. Even though (or especially because) the film supposedly makes an effort to incorporate indigenous Hawaiian perspectives and advisors, we must call attention to how the film still relies on and recycles cinematic tropes about Hawaiʻi. Our critique is not about Cameron Crow’s intentions or the nonsensical plot lines of the film itself. Our critique centers on what Hawaiʻi means to a broad American audience, about how entitled they are to feel at home in Hawaiʻi, and about how settler colonialism in Hawaiʻi supports the larger U.S. settler colonial, imperial war machine.

The Real Context of Aloha: Settler Colonialism in Hawaiʻi and the Pacific

The historical or political context of the indigenous Pacific is frequently evacuated of any significance in the American cinematic imagination. The Pacific is viewed primarily as a site for anthropological investigation, white romantic fantasy, and as a staging area for U.S. imperial interventions to secure its military and economic interests in the region. This is something scholars and activists have been discussing for a long time. We suggest reading work by Haunani-Kay Trask, or Vernadette Gonzalez’s Securing Paradise for an introduction. We especially encourage thinking through the politics of what Teresia Teaiwa has called “militourism,” a process by which the colonization of the Pacific was made possible by a feminization of the region and its peoples in a manner that naturalized American military presence in the Pacific. This has created an environment wherein military force ensures the smooth running of a tourist industry, and that same tourist industry masks the military force behind it.

What we see in the film Aloha, is a representation of how militourism facilitates white redemption for the individual, i.e. Bradley Cooper trying to better himself in the film. Thus, a rehashing of the old colonial trope of Hawaiʻi representing the promise of white renewal, specifically, a recuperation of hegemonic white masculinity that gets a “second chance.” Does white masculinity really deserve a second chance?

While the film’s title Aloha, points to ways Hollywood continually appropriates Hawaiian culture, our interest and offense is not primarily focused on the deployment of aloha as a brand or name recognition for this film. Though the plot of Aloha is certainly maddening, the appropriation of aloha has almost progressed to the status of being banal. Welcome to Hawaiian reality. Aloha is so rapidly vacated of any spiritual significance in the American colonial imagination (thanks to tourism) that a film studio readily invokes the term, believing the title alone will draw paying audiences. And, as if naming the film Aloha was not enough for the film studio, screenwriters incorporated the word throughout the film in a myriad of ways that only reified the nonsensical plot lines, as its use was so repetitive it was confusing and it deprived the term of its power. Remember, Aloha was actually the studio’s better, second choice over the rather gross first title Deep Tiki (recalling the similar situation around the 2009 movie Princess Kaʻiulani, which was originally to be called Barbarian Princess!).

Aloha is a dynamic expression of what it means to be Hawaiian which is intertwined with our deep intellectual, political, and emotional commitments to our culture, our oceans and lands, and one another. But, aloha does not always need to manifest itself in welcoming, harmonious or necessarily passive behaviors. As Maile Arvin and Lani Teves have written elsewhere, anger too can be an expression of aloha. Or, as explained by Noelani Arista and Judy Kertesz, “It is time that Hawaiians put out a sign that says, “no more love; aloha denied.”

What’s Missing from Asian American Critiques of the Film

Asian American critics seem pretty upset that Emma Stone is portraying a mixed race Asian character, but the critiques we have seen thus far have neglected to take issue with Stone’s character also portraying a mixed race Native Hawaiian. In some cases, it is even unclear if the authors of the critiques realize that Native Hawaiians exist, as a distinct people from Asian Americans local to Hawaiʻi. It is thus truly maddening that Emma Stone’s lack of Asian American features has taken center stage in public controversies over the film! This coincides with the appropriation of “hapa” which is a Hawaiian term connoting mixed Native Hawaiian ancestry, but has been adopted and used by Asian Americans of mixed ancestry. The critiques surrounding around the casting of Emma Stone due to her lack of Asian American ancestry (and not her lack of Native Hawaiian ancestry) signifies the erasure that is necessary for continued US settler colonialism of which all settlers including Asian Americans are beneficiaries. While of course, we would enjoy seeing mixed race Asian American and Pacific Islander actors on screen more often, we encourage everyone to rethink the endgame of fighting to be the “local” love interest of the white male lead. More generally, what is the point of fighting to be visible within films that refuse to relinquish the story of Hawaiʻi as a place of white romance, of white males being redeemed through obtaining young, female Hawaiian lovers?

Remarkably, Aloha is actually one of the only Hollywood films to make any gesture towards the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, through its inclusion of Bumpy Kanahele, who reminds viewers that the Hawaiian Kingdom was illegally overthrown in 1893. We could perhaps read this inclusion as commendable in some respects, and therefore, it is particularly upsetting that all the Asian American criticisms have overshadowed any discussion of the film’s attempt to engage the sovereignty movement (as shallow and incomplete as it may have been). Not only this, but Kanahele’s community, which is located at the foot of the Koʻolau in Waimānalo (in real life and in the film), becomes a specified place that is staked as Maoli through such instances as Kanahele’s negotiation with the U.S. military and by the crossing of the ghostly Night Marchers. There are references through the film of Waimānalo, including in background set photographs and the song Waimānalo Blues, for instance. Ultimately, these attempts are superficial, and do not change the film’s adherence to a white romance set in a paradisical Hawaiʻi, especially since they do not show where Waimānalo is in relation to Hickam Air Force Base, or where Hickam is in relation to Honolulu or Waikīkī–instead, all of Oʻahu is blurred together. Two of us (Liza and Maile) in Hinemoana of Turtle Island have genealogies that tie us to Waimānalo specifically. It felt bittersweet at best to hear Waimānalo Blues, a song that directly critiques tourism in Hawaiʻi and expresses deep aloha for our family home, played in this Hollywood movie, to audiences who will likely not understand the context of this beloved song and place.

We read the Asian American criticism of the film as yet another instance where Asian American and Pacific Islander racial categorizations fail to articulate the solidarity that the categories are imagined to bridge. Rather than express anger about the lack of Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian representation, or the ongoing representation of Hawaiʻi as a place devoid of complex political histories, we hear critiques from Asian American actor associations that focus on the general lack of diversity represented in the film. In one statement, the association (MANAA) took issue with stock Asian characters who were described in the abstract (i.e. “Indian pedestrian” or “upscale Japanese tourist”). The association seems to advocate for more nuanced representations, but neglects to mention why and how it could be that whiteness so easily inserts itself into Hawaiʻi, and how this practice has gone uncontested in Hollywood since the early twentieth century.

Cameron Crowe has apologized for his decision to cast Emma Stone as a mixed race white, Chinese and Native Hawaiian character. Like many settler apologies, this one is laughably besides the point! Kānaka Maoli and other indigenous peoples are accustomed to these kinds of settler apologies for their ignorance. It echoes the language of settler-states and their neocolonial forms of management that employ apologies and the language of “reconciliation” and “recognition.” Yes, it is a first step, but it is often the only step. It is reminiscent of the 1993 “Apology Bill,” signed by President Bill Clinton, that acknowledges the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. These apologies carry little weight after the fact because they are often qualified with an abdication of any responsibility for reparation on the part of the State, or Hollywood, in this instance. In other words, the apology becomes a stand-in for any sort of real institutional or systemic change. As Haunani-Kay Trask noted in her poem, “Apologies,” “And all our dead and barely living, rejoice. For now we own one dozen dirty pages of American paper to feed our people and govern our land.” Crowe’s apology is a move to settler innocence that can simply be viewed as a product of an ongoing tradition of settler-colonialism in Hawaiʻi.

Again, our critique is much less about what Emma Stone’s character looks like–for indeed, Native Hawaiians look a lot of different ways (and so do multiracial Asian American people). Even if there was a Native Hawaiian actress playing Emma Stone’s character, the film would participate in perpetuating very old settler colonial narratives, including making that character’s Hawaiian ancestry into something of a joke (as other characters in the film remark disparagingly about how often she says she is Hawaiian). We aren’t after an apology from Crowe. We are after decolonization and structural change that would end the seemingly tireless repetition of Hollywood cliches about Hawaiʻi. We also call for the resources to support other stories about Hawaiʻi.

Kapu Aloha and Aloha ʻāina

In one of its many plot points, Aloha repeatedly emphasizes the sky as a place of wonder, beauty and knowledge. Emma Stone’s character holds a childlike wonder for the sky, and is similarly rather naively outraged that someone would weaponize a satellite, because the sky belongs to no man. Kanaka Maoli certainly have reverence for the sky and the stars, but it is not merely a childlike wonder. Traditional seafaring, as just one example, relies on ancestral ways of understanding the stars and sky as a navigational map. Yet, the film and most of its critics overlook an ongoing struggle Kanaka Maoli are currently engaged in, on the slopes of Mauna Kea, a volcanic mountain on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi. This fight is in part about the sky; about the struggle between differing epistemologies regarding knowledge, human connection, and the quest for understanding our collective pasts. The struggle at Mauna Kea is about whose knowledge about the sky matters. It is about the ways Western science is touted as a privileged form of knowledge seeking, subsuming the sacredness of the land it operates on, to scientific and Western forms of relationality. Mauna Kea becomes something to commodify, to develop, to negotiate, and to use, despite thousands of years of Hawaiian spiritual and cultural relationship to that mauna. For the last three months, Kanaka Maoli protectors of Mauna Kea have been camped out on the road leading to the summit, blocking the construction of a proposed Thirty Meter Telescope (over 18 stories tall, and covering 5 acres) which would destroy an incredibly beautiful, rare and sacred site, and likely impact the environment and water aquifer for all those on Hawaiʻi Island.

Recently, at the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association Conference, a few of us were able to learn from Kanaka Maoli scholars involved with the struggle over Mauna Kea. We were especially excited by the work of Mary Tuti Baker who discussed the ways that aloha ʻāina (love of the land) discourse is used by Kānaka to build Lāhui and challenge the primacy of Western thought and ongoing U.S. military occupation in Hawaiʻi. She cited the actions of the Mauna Kea protectors who are using forms of kapu aloha to guide their actions on the mauna. Manulani Meyer describes Kapu Aloha as a discipline of compassion to express aloha to all, especially those who are perceived to be on opposing political sides. Meyer explains that kapu aloha “honors the energy and life found in aloha—compassion—and helps us focus on its ultimate purpose and meaning.” The protectors of Mauna Kea are guided by kapu aloha and we think that this is the kind of aloha that deserves our attention, not a Hollywood film. We would hope that in the future kapu aloha and aloha ʻāina would garner the support of the general public. These are the kinds of aloha that guide our actions, that honor the genealogies of Kānaka Maoli, that prioritize the protection of sacred sites and the self-determination efforts of Indigenous peoples everywhere.

Indigenous Pacific Films We Actually Recommend

There are so many other stories to tell about Hawaiʻi and Kānaka Maoli, and Cameron Crowe isnʻt the one to do the telling. For those upset by Cameron Crowe’s vision of Hawaiʻi, and for those who would prefer to never have to think about how distorted Hollywood representations of the Pacific Islands are, we urge you to support films and filmmakers who do center Native Hawaiian and other Indigenous Pacific Islander stories. Here are some of our suggestions for films about the Indigenous Pacific that we actually recommend. They are listed in no particular order, and we acknowledge that the following list is far from comprehensive. We welcome further suggestions for films we should all see in the comments!

Noho Hewa (http://www.nohohewa.com/)

Now streaming on Vimeo as a fundraiser for Anne Keala Kelly’s next project, which you should also support, Why the Mountain, “a documentary for and about Mauna Kea”: https://vimeo.com/124882949

2008, Dir. Anne Keala Kelly

Many of us screen Noho Hewa in the classes we teach, because it can be very eye-opening for those who may only associate Hawaiʻi with the tourist experience. The film addresses a number of political issues important to Kānaka Maoli, including the protection of iwi (ancestral remains) during the construction of a new Walmart in Honolulu and vacation homes, as well as from military live firing exercises, struggles over GMOs, water rights, and houselessness.

Living Along the Fenceline (http://www.guam.festpro.com/films/detail/living_along_the_fenceline_2013)

2011, Dirs. Lina Hoshino and Gwyn Kirk

From Guam International Film Festival website: “This ground-breaking film tells the stories of seven women who live alongside US military bases in Texas, Puerto Rico, Hawaiʻi, Guam, the Philippines, South Korea, and Okinawa (Japan). They take us into their homes, walk us through their neighborhoods, and introduce us to their communities. We see how military operations and bloated military budgets have affected their lives as we listen to their experiences and take in their surroundings.”

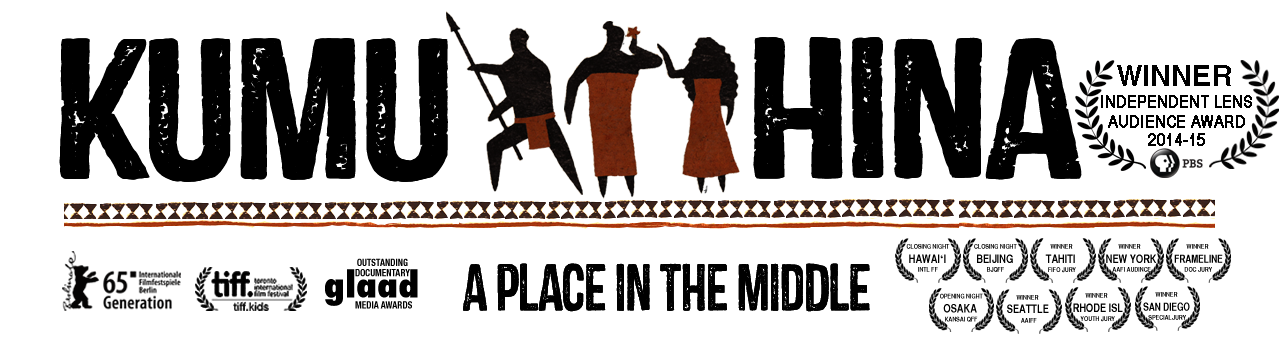

Kumu Hina (http://kumuhina.com/ available on iTunes)

2014, Dir. Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson

An actual love story, not just set in Hawaiʻi, but about the very real difficulties of having and sustaining love in a place that is supposed to naturally exude it! Love, or shall we say, aloha, here – expands aloha to ʻohana, community, to the ʻāina. Aloha in this film is lived through Hina’s kuleana to her community and her students at a Maoli charter school in Honolulu. Gender, sexuality, decolonization, and aloha are interwoven themes through the film and through Hina’s personal story. Hina’s struggle in love and life help to tell the larger stories of ways that colonial histories have shaped Maoli lives in intimate ways in the present.

Haku Inoa (http://hakuinoa.com)

2012, Dir. Christen Hepuakoa Marquez

This documentary follows the personal story of director Christen Hepuakoa Marquez, who embarks on a quest to discover the origins of her long Hawaiian middle name. In the process, she learns more about how she became distanced from her mother, tentatively reconnecting with her as an adult. This film is very personal and very brave, showcasing some of the difficulties that many Native Hawaiians face when living in diaspora in the continental United States. The film also shows the many ways those Native Hawaiians work very hard to repair and maintain connections with their families and homelands in Hawaiʻi.

The Land Has Eyes / Pear ta ma ‘on maf (streaming free on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/112031380 )

2004, Dir. Vilsoni Hereniko

From IMDB: “The Land Has Eyes is an 87-minute narrative drama about Viki, (introducing Sapeta Taito) a young South Pacific Islander who redeems her family’s name by exposing the secrets of her island’s most powerful and important people. Shamed by her village for being poor and the daughter of a wrongly convicted thief, Viki is inspired and haunted by the island’s mythical ‘warrior woman’ (Rena Owen, Once Were Warriors). The lush tropical beauty of Rotuma (part of Fiji) contrasts with the stifling conformity of her island’s culture as Viki confronts notions of justice and her own personal freedom.”

Boy (http://boythefilm.com, available on Netflix Instant)

2010, Dir. Taika Waititi

Boy is about a Maori boy growing up in the 1980s, with a great love of Michael Jackson, and an even greater love for his largely absent father. This film is absolutely hilarious, in the familiar way that kids can deliver the funniest lines in an absolutely earnest, deadpan manner. It is also full of heart, delighting in the daydreams of kids and gently following the larger-than-life hopes they have for their families, which cannot always be fulfilled. The quirky humor and vision of director Taika Waititi (of Eagle v. Shark, and Flight of the Conchords) is used to great effect here. What we love the most about this film is that it resists a narrative that pathologizes Maori families (as the more famous film Once Were Warriors may do), but highlights Maori love, desire, and dreams for the future.

The Deadlands (http://www.thedeadlandsmovie.com, available for rent on iTunes)

2015, Dir. Toa Fraser

This Maori action film follows the story of the son of a tribal chief who seeks vengeance after most of his village is slaughtered by a rival tribe. Set entirely in an Aotearoa that predates European contact and colonialism, and scripted entirely in Maori language (with English subtitles), the film immerses its audience in an awe-inspiring Maori world. The film complicates notions of humanity, nobility and familial duty, while maintaining a deep respect for Maori epistemologies and relationships with land and ancestors. There are also a few very fierce female characters we loved. James Rolleston, the charming star of Boy, also stars here, playing Hongi, the main character of The Deadlands.

The Orator / O Le Tulafale (http://theoratorfilm.co.nz/, available on Hulu)

2011, Dir. Tusi Tamasese

From the film’s official website: “The Orator (O Le Tulafale) is a contemporary drama about courage, forgiveness and love. Small in stature and humble, Saili lives a simple life with his beloved wife and daughter in an isolated, traditional village in the islands of Samoa. Forced to protect his land and family, Saili must face his fears and seek the right to speak up for those he loves.”

Close of the Day (http://mickidavis.com/, excerpt here: https://vimeo.com/29652089)

Also on view at the Pacific Islander Ethnic Museum in Long Beach, CA through July 5

2011, Dir. Micki Davis

From the director: “This project was an exploration of my Chamorro heritage via the lives and memories surrounding my Grandparent’s small grocery store in Agat, Guam. Taped in the month of July 2010, several hours of home footage, interviews with villagers about the store, and semi-theatrical staging of daily rituals composed into my version of a visual fugue. The theme stated in the title of the show and restated in the opening video reoccurs in several variations throughout the video and installation: Close of Day is a social hour, it is time of day when our ancestors are most active and it is the time when we reflect on our present day, our past and speculate our future.”

Sione’s Journey (https://myspace.com/264395542/video/sione-s-journey-what-is-a-tongan-dedicated-to-johnny-folau/33006522)

2011, Dir. Folola Takapu

From De Anza College IMPACT AAPI: “About a young Tongan American man’s search for answers to the question, “What is a Tongan?” The film humorously and touchingly presents stereotypes about Tongans, and features interviews with Tongan immigrants (many who speak Tongan) and younger Tongan Americans discussing life in the Bay Area, including a professional dancer, an artist, and a fashion designer/entrepreneur. Produced by Folola (Lola) Takapu (with no previous filmmaking experience) when she was a student at UC Berkeley, the film has gained popularity mostly through word of mouth and Lola was even invited to Tonga to show her film at an academic conference.”

Other resources to help find films that center Indigenous Pacific Islanders:

- Pacific Islanders in Communication, a nonprofit media arts organization based in Honolulu

- Nā Maka O Ka ʻĀina, Hawaiian documentary and educational videos by producers Joan Lander and Puhipau

- New Zealand Film Commission, government initiative that helps fund and promote films made in New Zealand

- New Zealand On Screen, online showcase of New Zealand television, film and music video

Leave a comment